THE HISTORY OF THE PARISH CHURCH OF ST. JOHN THE

BAPTIST, BLISWORTH

Forward: George Freeston in 1965/6 presented a series of talks on Blisworth Church which spanned many months. The notes that he typed for these talks now reside in the Northampton Record Office (NRO) as document 35p(ecclesia)/29. He also presented the same material into issues of the Parish Church News, from 1963 onwards, and issues from late 1970 onwards are abstracted to the website. I have photographed all his 60 pages containing some 8000 words and, whilst retaining his words, have recast his paragraphs so that coherent accounts of various aspects could be presented separately. This was necessary as his original style often mixed the topics. He clearly intended in 1965 to glue in various photographs but there is no record of which precisely would have been used. It is likely that many photographs have been lost. I have accordingly inserted some of my own.

There are accounts on the history of the fabric of the church, on the interior, the ornaments, plate, the bells and some of the earliest incumbents. Occasionally I have inserted pieces of text, in italics, needed in explanation that I have derived from other sources, mostly from documents in the NRO. I have also embedded the odd comment that I found irresistible. However, all these additions are at a minimal level.

At this time there are two substantial omissions. One is the account of early incumbents but this is partly covered in the website article linked above. The other is George’s detailed account of the monuments and inscriptions in the Church including much to be said of the Wake family and the tomb. They are omitted for only the reason that it is village family history and not specifically the history of the Church. However, it must be said that George Freeston’s work on very early local history has not received much attention as yet and this document at the NRO is a good place to begin an appreciation of it (see page 33 onwards).

T. Marsh December 2005

Download this document as a PDF file (150KB text only).

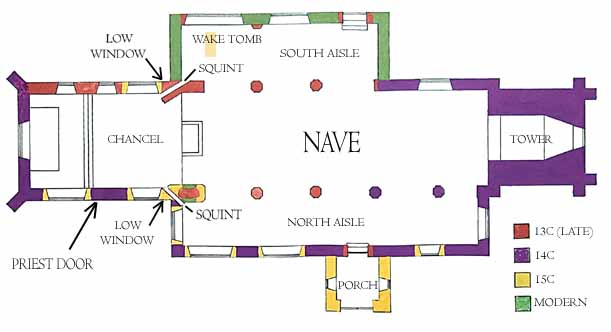

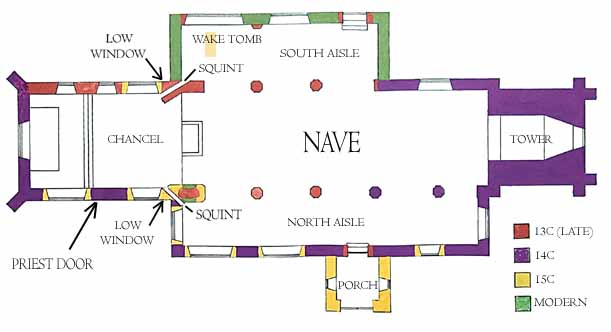

Our Parish Church was commenced in the late 13th century when a great fervour of church building swept through Northamptonshire. It is thought by some that an earlier Church stood on the same site. This 13th century building consisted of the chancel, with the nave extending to only three bays, with both north and south aisles. In about 1320/1340 the nave was extended to its present length of 61 feet 6". The north aisle was also extended, but the three bays of the south side remained as original. Both north and south doorways are of the 13th century with the characteristic edge rolls. The tower followed later in the 14th century. The chapel at the east end of the south aisle is of the 14th century, and now contains the table tomb of Roger wake and his wife Elisabeth Catesby. In the 15th century three large windows were inserted in the chancel, but two of the original 13th century small windows were left untouched. Both of these are on the south side. The fine five light east window has tracery of unusual type and this was in all probability added in the 14th century when the east and north walls of the chancel were either rebuilt or refaced. There is also a blocked north doorway in the chancel - often referred to as the ''priest's doorway." It is not known when this was blocked. Also of great interest on both north and south sides of the chancel are the blocked low side windows. Below - the priest door.

Last month's notes were read by at least two people, both of whom deserve mention for one of them is 90 years old and the other coming up to 80. The latter, Mrs. Lee of Connegar Leys, says that she fully enjoyed the notes and that she considers the re-telling of the history of the Church an excellent idea. From the 90-year-old came a very welcome correction. Last month I stated that the north "priest's door" had been blocked at an unknown date but Mr. William Whitlock informs me that he well remembers [in his teens, 1880s] this door being open and in regular use. The only people to officially use it were the Rector and the members of his family. At that time the chancel was furnished with only two ancient stalls, now used by the choir-men, and it was in these that the Rector's family sat . . . in fact they used the chancel as a private pew. The choir sat in the belfry. With the installation of the organ in 1889 the "priests doorway" was blocked up, the boys' choir stalls were erected, and the choir was moved up to the chancel, but the introduction of surplices and cassocks followed many years later. Having now made this correction, thanks to Mr. Whitlock we will return to the notes in sequence from last month's tour of the Church. The tower was added to the Church at the end of the 14th century and the official description is thus: " The lower is of three stages divided by strings, with moulded plinth and pairs of four-stage buttresses at its western angles, above which there are small diagonal buttresses. In bottom stage is a restored west window of two trefoild lights, but the north and south sides are blank. The middle stage has a small trefoiled opening on each side, that on the north side covered by the clock dial, and the pointed bell chamber windows are of two trefoiled lights with a quatrefoil in the head. The tower terminates in a battlemented parapet without pinnacles. Apart from providing homes for the many birds and bats, the chief object of massive belfries was to house the varying number of bells. The earliest mention of bells at Blisworth occurs in 1552 when there were “three great belle and a Sanct. bell”. There appears to have been a complete overhaul of the bell frame and the bells in 1624, which date appears on one of the massive oaken beams now supporting (rather precariously) the frame on which our present five bells hang. At that time, 1624, the second and third bells were most probably added, for both these bells are inscribed with the date 1624.

In 1626 the smallest bell was recast, and yet again in 1758. Number 4 bell was recast in 1758 and number 5 bell, our largest at 42” diameter, was recast in 1663 and again in 1758. In 1700 it is recorded that there was a Priest’s bell which carried the date 1635 but no mention of this bell appears at a later date. More detail written by G. Freeston on the Blisworth bells may be found included in the feature “Restoration of the Church Bells”.

Having dealt with the general dates of the construction of the church it is now appropriate to dispense with our notion of the present “look” of the building. In terms of both exterior and interior there have been many changes in the lifetime of the building. there were some alterations before and during the Reformation, for example to the windows. The great windows were installed in the 15th century but little modified since. Some have lost their stone mullions and the window at the west end of the north aisle appears to have been altered with the lower part blocked up. Other windows have been restored. The great windows would have originally been filled with stained glass pictures and only remnants of these past glories is to be found in the tracery of the north west window of the chancel. All other stained glass is modern. The present porch was built in 1607.

Major changes took place in the 19th century - often referred to as the “mishandling period” - whence so many of our parish churches underwent complete alterations to furnishing and fabric. This surge of restoration was carried out by over-zealous squires and lords of the manor and even moneyed parsons too. If the “old-folk” were to come back I think they would be surprised at the change to the skyline made in 1855/56.

Architect E. Law of Northampton and builder Ireson replaced the very shallow pitched lead-covered roof to both chancel and nave with a steep gabled and slated structure which some would regard as more attractive and certainly less liable to maintenance problems. An examination of the record of marriages in the 1850’s show remarkably few, 2 instead of the norm of 12, in the year 1852 and a reduction in 1855. It seems likely that something serious happened to the roof in 1852 which called for a temporary repair and a re-construction a few months later. So, in the case of Blisworth perhaps not necessarily over-zealous.

Now lets turn to the changes in the interior of the church, each telling of the social, economic and religious upheavals of the country. We can assume that in the pre-Reformation period we should have seen a carved stone altar placed against the east end wall and well decked with the ornaments of the time. Reference to this has come down to us in the wills of two important Blisworth residents. In 1528 Emma Wake died and left by her will “to the hygh altar a curcho for a corporas..”, and in 1557 John Curtis (priest and schoolmaster) by his will “I give to the town of Blysworth to the use of God’s service to be mayntayned within the said church a chales (chalice) with a paten, a corporas with a case and two vestments to serve God”

Please note: curcho = a kerchief. corporas = a cloth on which the consecrated elements were placed. reredos = ornamental wall-covering behind the Altar.

The religious changes brought about by the accessions of Edward VI, Mary and Elizabeth were the main causes of much destruction and re-arrangement within the chancel. With Edward VI the “Hygh Altar” was removed and a table called “The table of the Lord” was placed in the centre of the chancel, the congregation standing or sitting around it. On the accession of Mary, many of the old stone altars were restored, but on the accession of Elizabeth the “Lord’s Table” was again introduced. These Elizabethan tables were often rich in wood carvings.

It is said the towards the end of the 16th century Archbishop Laud was so shocked at the irreverent attitude of the people when the communion table was placed in the centre of the chancel that he gradually influenced the church officials to replace the Tables against the east end wall, as in former days, and erect rails for people to kneel at during the Service of Communion. These rails were also intended to prevent dogs from defiling the Table.

Our own very fine communion rails date from the mid-17th century. It is fairly certain that from this time, little or no change took place within our chancel until the mid-19th century when we know of extensive rearrangement of pews by the same architect and builder who replaced the roof (1856). At that time the floor was covered with the then fashionable encaustic tiles as was a wall at the back of a renewed Table. Our present setting was created in 1910 when the Elmhirst family (Blisworth House) gave the beautiful carved reredos and the raised oak floor. The Victorian Table was then encased within an oak superstructure specially made to carry the numerous new needlework frontals. The only change to take place from 1910 has been the removal of the 1855 Communion Table from within the case, and this now stands next to the South Door.

The Church Plate We do not possess any church plate from before the Reformation. Henry VIII suppressed all religious houses in his realm in 1539/40 and appropriated their possessions. He instructed his commissioners to leave only sufficient silver vessels for the use of the church. Many incumbents and churchwardens began to dispose of their church plate. Between 1547 and 1552 a great many churches were said to have been broken into but often this was a pretence to cover the disposal. In 1552 King Edward “collected” much of what remained.

The oldest pieces of plate which Blisworth church possesses are in regular use. The oldest piece, a Communion Cup made about 1570, is a fine specimen of the silversmith’s craft. the other is a delightful paten that was in all probability made as a cover for the 1570 cup in about 1636. I used a reference work, viz. “The Church Plate of the County of Northampton 1894”.

The Rev. William Barry, MA Trinity College, Cambridge, was instituted into the living of Blisworth in 1839. Thus he followed the notorious and often absentee Rev. Ambrosse. He evidently disapproved of the old Rectory for in 1842 he built a fine new Rectory with stables and substantial Coach House which have just been demolished (~1964) in order to widen the High Street. During the Rev. Barry’s 45 years as Rector he oversaw many alterations and made many gifts to the church, for example three pieces of plate; an 1845 silver paten, an 1845 silver cup and an 1846 silver Alms dish - each bears the words “Presented to the Church of Blisworth by the Rectore A.D. 1846”. The remaining and largest piece of Church Silver is a fine Flagon made in 1870 which bears the text: “Christus est immollatus nostram pascha”. The donor of this is not recorded. There was also some pewter plate which was thought to have been lost before the coming of the Rev. Barry.

It might interest readers to know that the value of the Church plate (1965) is £460 - nothing of value is kept in the church of course.

Chancel Ornaments At the rear of the Communion Table and on a ledge which is part of the reredos stand two brass candlesticks and either two or four brass flower vases. We have no record of who donated these pieces but they were presumably given during the past 80 years.

The centre piece is a nicely proportioned brass cross, perfectly plain, standing on a square stepped plinth. The cross carries the inscription: “In memory of William Whitlock, Sexton 1872-1905”. With passing of the years and the vigour of the polishers it is becoming less and less readable.

This William Whitlock (nicknamed “Clocky”) was a colourful character - much in keeping with his forebears and his name-sake follower, also a sexton for a time (nicknamed “Witty”). The first William was sexton, parish clerk, member of the Blisworth Flower Club Committee, clock and watch-maker and repairer and the parishioner that ran the village sparrow club. The second William (1873 - 1966) was a wit, a leg-puller, carpenter, undertaker and sexton.

To return to the two candlesticks, it is fairly certain that the candle holder itself, and a candle, have been in unbroken use within the Church for as long as the building has existed. Even after the Reformation, a candle would have been essential to light the Church during services. After many centuries the candle, the wax taper and the rush light holders gave way to the oil lamp. It is to be regretted that with the introduction of this new form of lighting that all of the wrought iron brackets and holders in Blisworth Church were discarded as worthless.

We do however know a little about the numerous “lights” that were in the Church in medieval times. It was a general thing for parishioners to bequeath certain items or money to the Church. Below is a selection from some wills which relate to “lights”.

William Denton - “a scheepe to ye lyghte before our lady”, this sheep would be sold and the money used for candles to his wishes. Elizabeth Tymys - “ a stryke of barle” for the same light. Richard Denton - “a pounde of wax for a light”. Beeswax from the honeycomb was one of the main ingredients of the candle or taper - besides burning with a steady light it gave off a pleasant aroma. Mention is made in some wills of whole hives of bees being driven to the Church for the production of wax. Such a hazardous practice has ceased. Finally, in 1526, William Water requested in his will that his wife should provide “a lyghte to burn at all service time on Sundaies and holidaes whilst she liveth”.

Most significant in the maintenance of lights were the allocation of numerous small fields around the parish, probably by the Wake family. In 1895, shortly after the newly formed Parish Council was formed, a Rev. Cox of Holdenby was asked to translate Latin scripts referring to these Blysworth Town Lands. The lands were lost at the time of the Reformation but regained afterwards and were then applied to the provision of certain ornaments in the Church. The interesting thing about these “Town lands” is that they have descended to this day and have commuted into our County Council and Parish Council fields, the majority of which have a community status. The NRO documents 35pe/191 & 192 are of importance in establishing the above detail - one of these, 191 The Report by Rev. Cox of Holdenby has been transcribed to this website.

There is little doubt that in pre-Reformation days there would have been a wealth of colour in the Church, for the walls would have been covered with murals and the woodwork painted or gilded. The Reformation brought a wholesale stripping which left the chancels very bare and whether by compromise or in a true effort for the edification of the people, Queen Elizabeth ordered that the bare walls be covered with panels on which the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer and the Creed be painted. Only the panels containing the Ten Commandments survive at Blisworth and these are not originals. Our two tablets have been subject to change, for when the new reredos was installed in 1910 they were moved from the side aisle and once more restored to their rightful place of honour in the Chancel. The correct name for these tablets is The Decalogue (ten sayings).

Modern Items Of three chairs, two are in the late Victorian “Gothic” manner. They are often referred to as the “Bishop’s Chairs” for they are only used by the visiting Bishop or special clergy. The earlier ones that these two replace would have been finely carved and going back to medieval times there may instead have been a stone Sedilia set in the south wall of the Chancel. But there is no sign of this earlier form.

Between the World Wars the Litany Desk was made and donated to the Church by Robert Shakeshaft who was the millwright and carpenter at the Westley Bros. & Clark flour mill in the village. The remaining items of furniture are post-war gifts.

In 1947 the Mother’s Union Banner was dedicated. This banner stands on an interesting base, made locally of oak and wrought iron. On the scrolls are carved oak shields on which are the regimental devices of three corps; The Royal Engineers, The Grenadier Guards and the Royal Air Force, being the sections of the armed forces in which sons of the donor served. The banner was given as a Thank-offering to God for their safe return from the war.

The two latest gifts are the Alms Dish and the oak Credence Table. In medieval times the Credence Table was often constructed in stone and its use then, as now, was in the preparation of the bread and wine for Communion Services.

Chancel Windows In the north wall of the Chancel are two large windows, one of which contains some interesting panels of medieval stained glass. Whether the majority simply collapsed or was taken out at the time of the Reformation is impossible to determine.

Early in the 19th century the New Oxford Movement encouraged much more colour and decoration. Like all fashions it was often overdone to the point of excluding too much light. It was not until 1872 that the first of our Chancel windows was so bedecked, when a memorial window was placed to the late squire and his wife, George and Mary Stone. This window is a fine piece of craftsmanship and its general colour and design are based upon the nearby remnants of medieval glass.

The East Window contains a memorial to Rev. William Barry and to Francis his wife. This could have been erected circa 1885. The large window on the south wall contains a memorial stained glass to memory of a son of the Rector, who died only nine - a rather heavy example of Victorianism.

The generally named “Low Side Windows” are a common

feature of local parish Churches but now mostly blocked up. Village historians

tend to be pleased to recount their own conjectural accounts of the usage of

these windows and I well remember the late Rev. W.W.Colley telling of how these

windows were used by the lepers who were not allowed to enter the Church. In

fact he referred to them as “Leper Squints”. Our Church has two, on the

outside of the Chancel; on the south wall it is almost square while on the north

wall it is a delightful decorated one with a square Label and a pretty little

trefoil head underneath.

The generally named “Low Side Windows” are a common

feature of local parish Churches but now mostly blocked up. Village historians

tend to be pleased to recount their own conjectural accounts of the usage of

these windows and I well remember the late Rev. W.W.Colley telling of how these

windows were used by the lepers who were not allowed to enter the Church. In

fact he referred to them as “Leper Squints”. Our Church has two, on the

outside of the Chancel; on the south wall it is almost square while on the north

wall it is a delightful decorated one with a square Label and a pretty little

trefoil head underneath.

Theories abound but I favour the research carried out

by the late Christopher Markham - there was certainly no evidence that the

lepers were so numerous in England. The general idea that they were there to

deal with certain people who were unable to enter the Church, seems most

plausible. The setting of the windows permits sighting of the Rood with the

figure of our Lady which permit the outsiders to worship. Perhaps those outside

were serving some conditional penance.

Theories abound but I favour the research carried out

by the late Christopher Markham - there was certainly no evidence that the

lepers were so numerous in England. The general idea that they were there to

deal with certain people who were unable to enter the Church, seems most

plausible. The setting of the windows permits sighting of the Rood with the

figure of our Lady which permit the outsiders to worship. Perhaps those outside

were serving some conditional penance.

Santuary Many people name the east end of the Chancel the Sanctuary, referring also to the belief that should a fugitive take shelter there he could escape justice. In olden days this was partly so but the whole Church together with the Churchyard constituted a unit of sanctuary, provided such places had been dedicated. In the 9th century the privilege of sanctuary was for seven days and nights and by the 12th century it was extended to 40 days. In this time a suspected felon would need to establish his innocence or be expelled at the end by the coroner subject to an oath of abjuration whereby the offender pledged himself to cross the seas to some other Christian country within a given time. He or she would be sent away penniless, clothed in a sackcloth and carrying a white cross.

Whilst in the Church the fugitive was to be fed by the parishioners and watched carefully for if a fugitive should escape the parishioners were fined. If anyone interfered with a fugitive whilst on the road to a port (such as Dover, Yarmouth or Bristol) it was considered a grave punishable offence. The fugitive was compelled to stay on the highway and was passed from constable to constable on his way. The rights of sanctuary were abolished in 1623.

(George’s script, page 11, includes Northamptonshire stories of various sanctuary related incidents in the 14th century)

The Rood The original purpose of the wooden dividing screen was to separate the clergy from the congregation - the Chancel was reserved for the priests. In medieval days every Church had its rood screen with a rood loft and the Rood. The woodwork of the screen tended to be the highest point in the splendour of the building and shown regional characteristic variations. Our screen was built at some time in the 15th century. All that remains to tell of the rood loft is the very fine rood loft stairway, completely embodied in the thickness of the stone wall, on the north side of the Chancel arch. The loft probably did not survive the Reformation and most of any other fine craftsmanship would doubtless have been plundered by Cromwell’s men. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries anything left was left in peace and neglect - and so it must have been for our screen. A major repair was carried out, presumably, at the time of the re-roofing of our Church. At that time an ugly beam was added for support, not of oak but of stained white wood which seems most unfitting. In 1911 minor repairs were carried out to the screen - it is hard to believe it is 500 years old.

In pre-Reformation times there would be the Rood, ie. the “Cross of Christ”, fixed to the centre of the loft. Flanking the figure of Christ would have been the figures of the Virgin and of St. John. The rood screen, together with the statues, would be decorated by foliage and candles on festival days. The lower panels would be painted with figures of saints and a candle would always be left burning in front of the Rood. During Lent, the whole screen would have been covered by a veil.

Miscellaneous Architecture

As we do not have a crypt within our Church to write about, we will take a

second look at the bell tower. This massive structure is in three stages. In the

bottom stage is a restored window on the west side, but the north and south

sides are blank though carry an early example of polychrome stonework (limestone

and sandstone arranged in bands). The second stage has a small trefoil opening

on each side and is reached by a long and almost vertical ladder. The opening on

the north side is covered by the clock face. The top stage, or bell chamber, has

a trefoiled light on each side. These are fitted with louvres to deflect the

bell tones over the village. The windows are topped with a quatrefoil.

Miscellaneous Architecture

As we do not have a crypt within our Church to write about, we will take a

second look at the bell tower. This massive structure is in three stages. In the

bottom stage is a restored window on the west side, but the north and south

sides are blank though carry an early example of polychrome stonework (limestone

and sandstone arranged in bands). The second stage has a small trefoil opening

on each side and is reached by a long and almost vertical ladder. The opening on

the north side is covered by the clock face. The top stage, or bell chamber, has

a trefoiled light on each side. These are fitted with louvres to deflect the

bell tones over the village. The windows are topped with a quatrefoil.

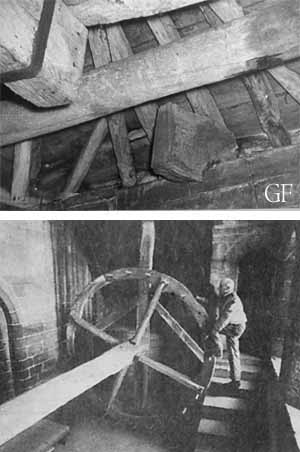

The tower terminates in a battlemented parapet without pinnacles, see above. The total space of the bell chamber is taken up with the massive frame of oak timbers in which are hung the five bells. It is on one of these beams that the date “1624” is cut. It probably signifies when further bells were installed.

Prior to 1960 the roof was a four square pitched

structure, covered with sheet lead and supported on a radial joist frame, the

centre of which was held up by a single king pin of oak which in turn was

carried on two great crossed horizontal beams - that is, originally; one of the

cross beams has a four foot piece taken out of it - an inexcusably erroneous and

stupid action. Evidently at the time of bell re-hanging, possibly around 1624, it

was necessary to install a windlass capstan to haul the bells up the tower. Here

is the photograph in which one can see the two sections of the beam and the

windlass roller occupying the gap between. [beneath is a suggested form of

the capstan that would have been used]

Prior to 1960 the roof was a four square pitched

structure, covered with sheet lead and supported on a radial joist frame, the

centre of which was held up by a single king pin of oak which in turn was

carried on two great crossed horizontal beams - that is, originally; one of the

cross beams has a four foot piece taken out of it - an inexcusably erroneous and

stupid action. Evidently at the time of bell re-hanging, possibly around 1624, it

was necessary to install a windlass capstan to haul the bells up the tower. Here

is the photograph in which one can see the two sections of the beam and the

windlass roller occupying the gap between. [beneath is a suggested form of

the capstan that would have been used]

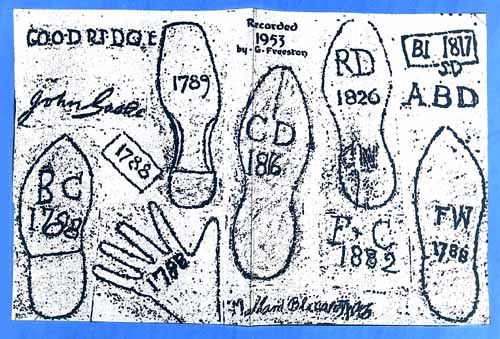

The lead roof carried some interesting markings. No doubt, many of the people who went up the tower in long ago days were locals. Hundreds of them at least left their mark by inscribing their names or initials in the lead, and in many instance they placed their boot, or their hand, upon the lead and scribed the outline, leaving a bold and interesting fashion parade of footwear of the time. I regret now that I did not take a photographic record of these markings before the lead was removed. Some of the old village names are recorded in the rubbings I took.

The new 1960 roof is flat and is covered in copper.

In fact the fabric of the Church carries interesting

markings elsewhere. Lets begin with the low side window, now blocked up, on the

south wall. Here on the west jamb can be seen a scratched dial measuring about

four inches across with about thirteen divisions marked off in its lower half.

There is a hole in the centre for a small sundial gnomen. Similar dials can be

found on the south wall of most Churches and they date from between the Norman

Conquest and the Reformation. The incised lines are to indicate times of

observance of services and mass etc. Moving towards the west, on a window pane

of the window nearest to the tower, is something quite different - a diamond

cut-out inscription which reads: Ed. GF has not inserted this into his

script and it can no longer be found on the window. This is very popular manner of leaving a mark, or doodle, on a

building. What prompted this James Howard in 1799 to reach up and cut his name

with a citation to George III, 1798? The Great Fire of Blisworth was a recent

memory, we were at war with France, the canal had established Blisworth as a

temporary inland port . . . Other scratch markings occur on the stones of the

north porch built in 1607.

In fact the fabric of the Church carries interesting

markings elsewhere. Lets begin with the low side window, now blocked up, on the

south wall. Here on the west jamb can be seen a scratched dial measuring about

four inches across with about thirteen divisions marked off in its lower half.

There is a hole in the centre for a small sundial gnomen. Similar dials can be

found on the south wall of most Churches and they date from between the Norman

Conquest and the Reformation. The incised lines are to indicate times of

observance of services and mass etc. Moving towards the west, on a window pane

of the window nearest to the tower, is something quite different - a diamond

cut-out inscription which reads: Ed. GF has not inserted this into his

script and it can no longer be found on the window. This is very popular manner of leaving a mark, or doodle, on a

building. What prompted this James Howard in 1799 to reach up and cut his name

with a citation to George III, 1798? The Great Fire of Blisworth was a recent

memory, we were at war with France, the canal had established Blisworth as a

temporary inland port . . . Other scratch markings occur on the stones of the

north porch built in 1607.

A JC 1797 leaves his mark and there are two other

interesting doodles thus:- Ed. Again GF had intended to insert these but

overlooked to do so. What do you make of them?

A JC 1797 leaves his mark and there are two other

interesting doodles thus:- Ed. Again GF had intended to insert these but

overlooked to do so. What do you make of them?

Any building that is built of reasonably soft stone will carry various deep holes and slots. One pillar of the Church just inside the north door, to the right, has a collection of these cuttings, some of which are covered by pew fitments. It is now widely accepted that the cuttings have accumulated due to parishioners of the past in an attempt to invoke help for a sick or dying member of their household. A hair or piece of fingernail was taken to the Church and was held beneath the cutting whilst a stiff twig was rubbed to release powdered stone. It was taken home and applied to the person either externally or given as medicine in the believe that the “Holy Stone” powder would work a miracle cure.

There are markings, particularly on the external walls, which are supposed made by militia men in sharpening their swords and knives. In Yelvertoft Church there is a tomb half worn away by supposed Cromwellian troops.

The Churchyard Cross

On

the north side of the Church, by the path leading to the porch, are the steps

and socket stone of a churchyard cross. It consists of a calvary of four steps

built predominantly in ironstone, seven feet square at the base and terminates

with a socket stone two feet square. It is known that a sundial was erected for

a time in the socket. However, George Clark in 1855/6 depicts the Cross in the

form of what appears to be a limestone ornate column which matches the portal of

the new Rectory built in 1842. An old

photo c. 1885 that has come to light shows the cross to be surprisingly

slender. William Taylor, in his travels to collect information for

a history of Northamptonshire, was told in

1718 that there were only the remains of the Cross. This suggests that the Cross was restored c. 1842.

The column can be seen in image

16-21 on this

website. There is no sign of this relatively modern column or remnants, or memory, of it today.

It

is not easy to assess the age of the ironstone plinth. I would guess from the

general style of the stones that it was erected circa 1600 to replace an earlier

and possibly plainer edifice. To the north of the Cross, on the other side

of the High Street, is the site of the supposed Manor, as recorded on Ordnance

Survey maps. It is a conventional arrangement to have a Manor to the north of the

Church. Maybe in the 18th century the farm there was called "The

Manor". However, the same William Taylor in 1718 records that the

"Seat" (ie. where the Wake family lived) was

in the place now occupied by

the house called Blisworth House, which is to the south-east of the Church.

Hence the Ordnance Survey attribution is most probably erroneous, as it implies

the site of an ancient edifice to the north of the Church. In the

early 19th century the farm had been replaced by a large tithe

barn, the structure of which seems to have survived in part until c. 1900.

The question of the Manor is explained in more detail in the "Corrections

to the Blisworth Book".

The Churchyard Cross

On

the north side of the Church, by the path leading to the porch, are the steps

and socket stone of a churchyard cross. It consists of a calvary of four steps

built predominantly in ironstone, seven feet square at the base and terminates

with a socket stone two feet square. It is known that a sundial was erected for

a time in the socket. However, George Clark in 1855/6 depicts the Cross in the

form of what appears to be a limestone ornate column which matches the portal of

the new Rectory built in 1842. An old

photo c. 1885 that has come to light shows the cross to be surprisingly

slender. William Taylor, in his travels to collect information for

a history of Northamptonshire, was told in

1718 that there were only the remains of the Cross. This suggests that the Cross was restored c. 1842.

The column can be seen in image

16-21 on this

website. There is no sign of this relatively modern column or remnants, or memory, of it today.

It

is not easy to assess the age of the ironstone plinth. I would guess from the

general style of the stones that it was erected circa 1600 to replace an earlier

and possibly plainer edifice. To the north of the Cross, on the other side

of the High Street, is the site of the supposed Manor, as recorded on Ordnance

Survey maps. It is a conventional arrangement to have a Manor to the north of the

Church. Maybe in the 18th century the farm there was called "The

Manor". However, the same William Taylor in 1718 records that the

"Seat" (ie. where the Wake family lived) was

in the place now occupied by

the house called Blisworth House, which is to the south-east of the Church.

Hence the Ordnance Survey attribution is most probably erroneous, as it implies

the site of an ancient edifice to the north of the Church. In the

early 19th century the farm had been replaced by a large tithe

barn, the structure of which seems to have survived in part until c. 1900.

The question of the Manor is explained in more detail in the "Corrections

to the Blisworth Book".

During the 6th century a decree of Justinian specified that such a Cross should precede the building of the Church. It was from the 6th century also that burials in the ground around the Church became the practice. In any case, churchyard Crosses were erected throughout the medieval period and were often used as preaching points. Many were partly destroyed during the Reformation. During medieval times the churchyard was a busy place - the unused spaces were used by travelling merchants for their booths and stalls; fairs were held and at feast times there would be dancing and games and “Church Ales”.

From typed notes by George Freeston circa 1965 - transcript & additions Dec 2005

______________________________________________________

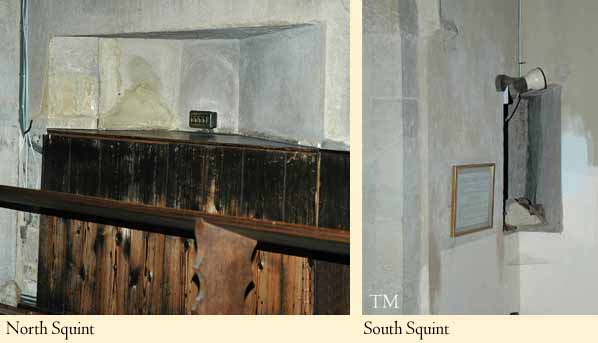

George Freeston made no mention of the two "squints" in the Church. This is probably because this article was written in the 1960s when the north squint was obscured by the 1888 organ (it was moved in the 1970s). A fine carved wooden architectural boss, which is shown below and is described in the church images section, was found in the 1970s hidden in the south squint when it was opened up. Perhaps this was the recent re-discovery of the squint. Both squints are angled so that a priest in each side aisle may observe the actions at the altar. One use of this facility was to provide suitable timing to the "elevations" undertaken in the two chapels relative to the action of the high priest (see Barnwell). At present, the south squint is visible only from the south aisle, whilst the north squint is visible only from the chancel. As the north squint runs through a relatively massive wall, the angling on its reveal is quite marked.