|

THE TRANSITION FROM

FEUDAL FIELDS ENCLOSURE REVIEW.

Brief Timeline, Parish area ~ 1930 acres*

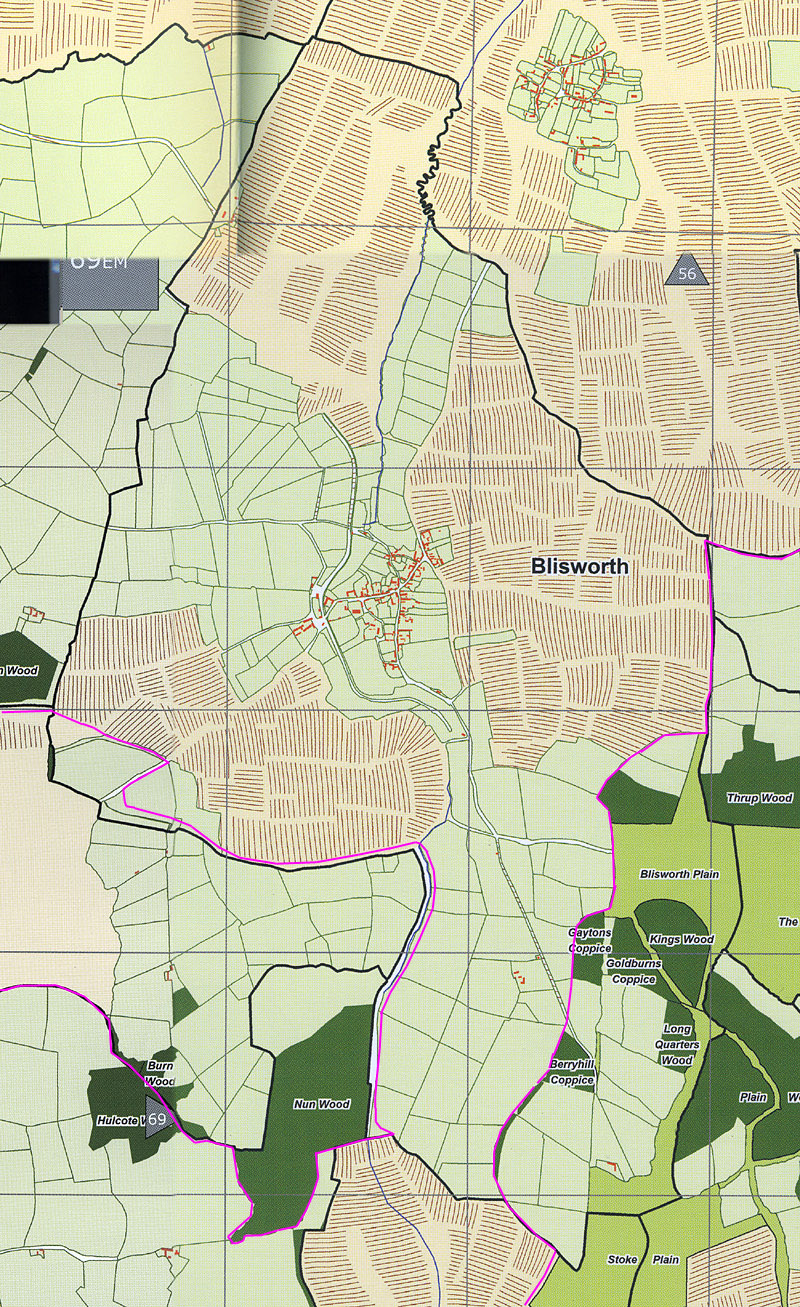

The process of making the enclosure award was the cumulation of a 300 years period in which certain farmers had already been favoured with large quotas of land for which they paid rent in parallel with many villagers who were assigned strips in various fields in the 'ridge and furrow' pattern. In the early days it was sheep farming for wool that appealed to the Lord of the Manor; by encouraging that on the enclosed fields the Duke was exacting a much higher rent from the much more productive farmers, who effectively became the first agri-businesses. In 1718, the curate remarked that "a small part of the parish was enclosed but this was not true. In 1808, the list of awarded farmers is as follows: William Gibbs, Robert Campion, Inigo Hands, William Goodrich, John Goodrich, Thomas Wesley, Stephen Blunt, William Worster, John Kingston, William Wilson, John Pettifer, John Dix, Sam Wilson, George Stone, John Goode, Thomas Parrish, Richard Gudgeon and the 'Rector'. The Rector was assigned ~250 acres in lieu of all the other parishes in the Deanery (or so it is thought), hence the creation of Glebe Farm to the west of the village. Note that the farmers Plowman and Brafield are not included; Plowman was forced to sell up in 1779 and Brafield had moved to Tiffield before 1800. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- With regard to the earliest dated information suggested in the Timeline table, the terrain suggests that a considerable area of the parish was wooded or otherwise 'waste' before 1500. Referring to the first map below, early wooded areas are outside the magenta lines, to leave a band of un-wooded land running from north to south through the entire parish. The land usage figures are guesses. 1265 - 1542: Towards the end of this period the Lords of the Manor were eminent characters. Having considerable influence was Thomas Wake V who owned a prodigious amount of land in the east-midlands and was three times the sheriff of Northamptonshire and an expert in Law. A growing awareness of the importance of enclosing a significant proportion of land (under presumed self-sufficiency constraints) to provide grass for animals and a level of fertilisation from keeping those animals so that (i) in terms of rotation the use of both corn and grass or other leys worked best for the land, (ii) the availability of a modest amount of meat (plus some for sale in town) and a significant amount of wool (either woven locally or for sale in town) was beneficial to the local economy, was gaining ground in the 16C (see "Pre-industrial England" by B.A.Holderness, 1976). Notable also was the founding of a free school in Blisworth in the late 15C which must have helped households start some specialist skills alongside peasantry. Perhaps 30% of what was hitherto ridge & furrow areas were enclosed as part of the cooperative (feudal) system. In this period there would have been an effort, though interrupted by the Black Death, to cut back the waste and woods. NB: it has not escaped notice that the wooded region named "Berry Hill" may have been really a bury hill site for the black death victims. Assarts in the early years were for heavy timbers for building while clearances would be needed to keep up with population increases in the late years. The next step was for cooperative feudal farms to be taken over by rent-paying farmers appointed by the Lord of the Manor. 1542 - 1649: We know little of the abilities of the seniors in terms of land improvement. Records are sparse for this period but some Church documents dated 1617, that deal with the protection of about 7 pieces of land worked in aid of maintaining lights at the altars mention some 17 senior members of Blisworth 13 of which were definitely tenant farmers. This fact indicates that the clustering of fields into separately run farms was well advanced by 1600 and that the sale and enclosure that occurred in 1649 probably involved land that was already enclosed. 1649 - 1660: A major process of enclosure took place in 1649, occurring in the Cromwell Commonwealth period 1648 - 1660. About 85% of the parish was sold and it seems likely that the best land already enclosed plus perhaps some common land was sold. Some 1600 acres altogether is thought to have been taken up by entrepreneurs. However it is almost a certainty that whilst leases were taken on some common land the peasantry were allowed to continue their cooperative style food-growing. Indeed, the scope for radical changes in only the 11 years while the commonwealth continued seems limited. In 1660 Charles II took back the lands which for Blisworth was the Honour of Grafton, and endowed the Duke of Grafton as the owner. Around this time it is probable that the mill pond was bypassed with a deeply dug stream cutting and so drained. It is also likely that the fish-pool was drained also since both these areas are referred to in Grafton's mapping for his 1727 survey as enclosed fields. In any event, if peasants were excluded from tracts of land in the period 1649 - 1660, it seems likely that those conditions would continue afterwards. 1727: The Duke's survey was commissioned in 1725. A map of the parish (map 4212 NRO) shows enclosed areas and fields designated as furlongs which one assumes to still be part of the open field area. The map is redrawn in D. Hall's atlas (The Atlas of Northamptonshire, by T. Partida, D. Hall and G. Foard) and that is reproduced with permission here. It is a combination of configurations: the hatched areas represent open fields and the green areas with a fields layout are supposed to be enclosed but the field layout shown is that which pertained after formal enclosure in 1808 yet an applicable date for this map is 1725. Note that roads are inconsistently shown and, in some areas, the path of the 19C canal is indicated (which is a graphical error).

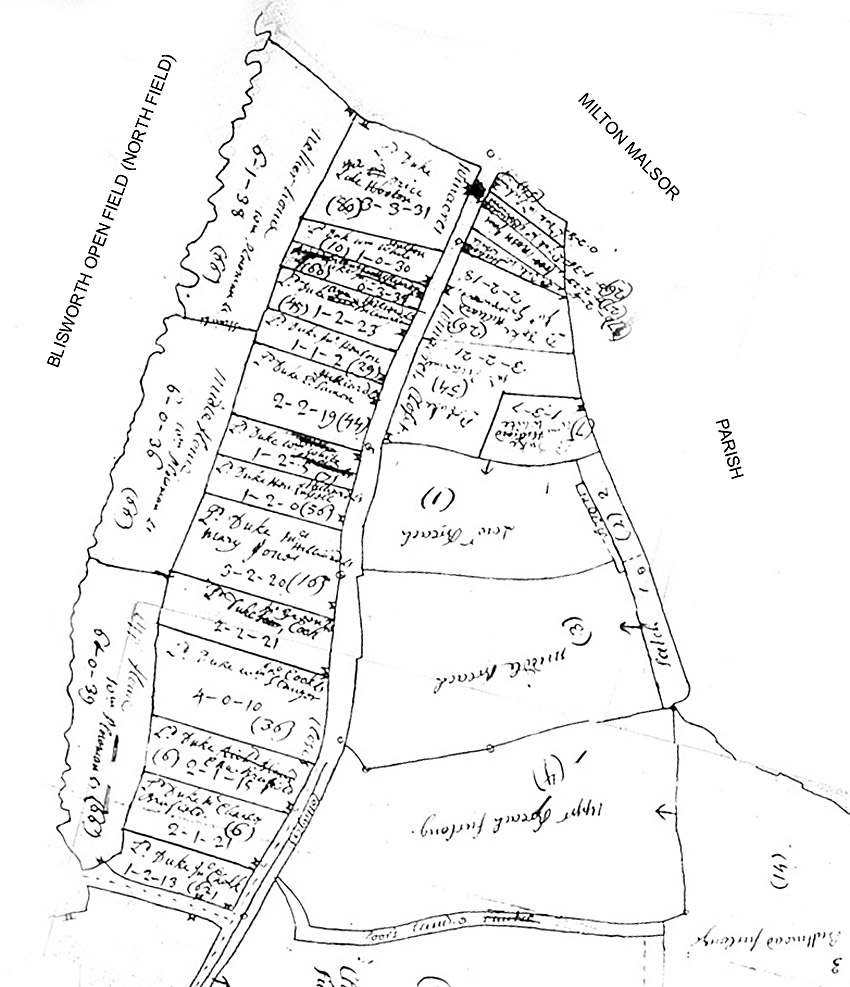

To properly appreciate what applied in 1727 one needs to inspect the detailed draft drawings of the estate which are given on maps no. 2323 and 2800 NRO. For example, consider the section shown below for a small area on both sides of the Northampton Road - enclosures on the west side (mostly) and furlongs ie. open fields to the east and bordering Milton Malsor parish. The level of subdivision was much finer. One remarkable feature is that there are at least 44 cottages in the village to which are assigned useful sized plots of land, 0.5 to 2 acres. Along the Northampton Rd and in some other places there are also over 46 further small fields, 0.25 to 4 acres. As an example, Mary Jones rented a cottage in Mill Lane (Chapel Lane) with 1.1 acre extending down to the mill brook and this cost her £1.75 per year. She also rented 2 acres at the northern end of the parish which cost a further £2.33 per year. It is evident that many households took similar tenancies and were obviously involved in part-time farming and that this activity must have sprung up after the entrepreneurial owners had departed in 1660. This adds to the picture presented in Holderness's book; it is tempting to assume that many households included (i) a member engaged in farm labouring on a yeoman's estate, (ii) someone working at part-time farming (probably growing basic food for the family and animals, such as potatoes and turnips, at the remote field while keeping the animals, such as pigs and chickens, on the 'home' patch) and (iii) someone engaged in a specialist skill such as that which supports farming or lace-making or weaving, cooking or butchering etc. Such households would be well off. An alternative interpretation is that the households are involved in full-time farming because they also have a number of lands in the open field area. However, such lands were abolished by 1808 and virtually all the small plots were coalesced by then. A further point should be made. The open field area of 820 acres is dominated by a total of 600 acres rented by as few as 10 farmers. That farming was a specialism, ie. a career, in the 1700s is a fact, at least for this parish. It has been pointed out that, in the absence of any remaining evidence, those farmers had taken a finely distributed array of lands that totalled 40 to 100 acres. With that input, we are supposed to believe that a typical career farmer held an enclosed area (in a number of plots) of about 40 to 100 acres and a similar total area as finely distributed lands. This is not a sustainable farming mode. More likely is the idea that, under the control of a village based committee (rather than the agent for the Duke), farmers and small-holders worked together to coalesce their lands in the open fields and, probably ahead of the formal enclosure, proceeded to graduslly enclose areas especially for grazing (meat and wool production).

As

mentioned above, the total area of all

open fields was about 820 acres while the total of enclosed fields was 850

acres, leaving about 200 acres of woodland. The honest answer to how much

of the parish was enclosed at the time would be 45% yet the curate Revd. Bullyer aimed to hide this fact when questioned for Bridge's History. Map 4212

also carries a "lie" in its

drafting. This map shows with

hatching the open fields correctly (we assume), yet at certain points omits field boundaries completely from an

enclosed area. It even draws in a bold pathway across a pale green wash

that links with the Ford Lane access and then wends its way along the edge

of the open field as far as the Gayton boundary. The pathway aligns with

the gateways between the fields yet neither gates nor hedges are shown.

Its route is shown in a map that is used on this

website to make other points. Why such a presentation was made is open

to speculation: The combination of (a) and (d) seem the most plausible. Turning to a further example of entrepreneurship by farmers, consider the following detail shown in the 1727 mapping, in particular in map 2323 NRO where they appears to be examples of field coalescence. See below.

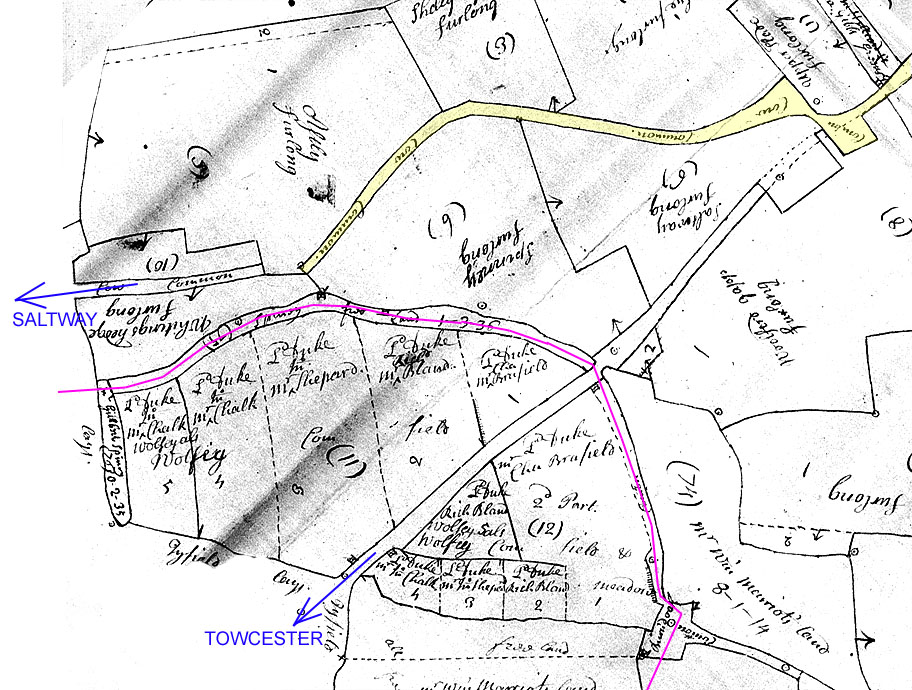

The Towcester Road is shown running towards the bottom left-hand corner. The Saltway is shown exitting the parish at left. It crosses the parish just south of the furlong called Woolford Gapp. The Gapp refers to the gateway construction across the Towcester Road where the old Tiffield Parish boundary (purple line) used to run before about 1685. The field named Wolfey Common Field was assigned to the Parish at about that time and was called Oxhay (the hay suggesting gateway - between parishes) when it was a part of Tiffield. Interestingly, although it straddles the road its tenure appears to be divided between four farmers without firm boundaries such as hedges. The areas could groups of lands. They could be cropped identically in a manner that could anticipate enclosure. The more interesting feature on this map segment is the pathway marked in pale yellow. It runs between a series of open fields on both sides, namely; Astley, Shelly Ley, Long Ley, Saltway furlong (mistaken geography here!), Spinney, Whitings Hedge furlong. It serves a small box enclosure that intersects and interferes with the Towcester Road and seems to offer priority access to the village although a number of gates appear to be omitted. The enclosure was designed to gather animals into a group for driving along the Towcester Road. Although the lands of each furlong field maybe still have been identifiable, they were clearly managed together for grazing sheep or cows. Possibly only half the total area of the six fields was assigned to communal grazing at a time. Nevertheless the central pathway highlighted in yellow indicates a level of group farming that necessitates enclosure for it to be successful. By the 'gapp' on the Towcester Road is a small trapezoidal field that once may have contained a building related to the gate. That site is now occupied by the Pynus terraced cottages built by Joseph Westley jnr. There is second enclosure or yard which crosses the Towcester Road. A possibility is that this yard facilitated stone extraction in the field to the south as discussed elsewhere. 1790: Continuing conversion from common land to useful arable land was in progress for we learn that by 1790 there was a list of assignees to the common-land. They were Robert Campion, Thomas Cave, Richard Gibbs, Cornelius Gudgeon, Joseph Hedge, Joseph Wills, Shadrach Wesley, William Pettifer - each holding 60 to 120 acres, each with permission to fence it off. This would not have happened unless the demand from the remaining "strip-farmers" had already waned - we know this because Shadach Wesley was a Baptist and Robert Campion was well-respected in the village. In some cases a large, originally open, field was subdivided and farmed by a subgroup of these tenants such as 'Long Stocking Field', the hither-part (nearest) of Nether (north) Field (and this had already occurred by 1727), Nether Palmers Bank and Willow Stump Furlong, etc. Unfortunately the location of many of these ancient named fields is unknown. But there is evidence here of an ongoing move towards complete enclosure of the common lands. There is further Northamptonshire evidence from a commentator on farming in 1791 that an ongoing enclosure was effectively taking up land that was not used, furthermore, the Duke of Grafton reported that there was no increase in families committed to the parish (ie. "registered" poor) during a period of enclosure in Pottesbury, 1774 - 1787. There should be no doubt that these were 'selected' statistics. By 1800 it seems doubtful that any villagers were still using common land for arable production. It is also doubtful they would have fenced a patch for animals because of the high likelihood of theft from somewhere so far from the village. The main issue was probably that they would have continued to exercise common land rights in terms of wood collection to fuel their meager winter heating and it is likely that the majority of villagers would try to do that. We have a few Court Leet documents that show that meetings still took place in 1725-1777. This narrow time span for still available documents is interesting; there was a fire at Euston House and this has resulted in there being no documents held by Grafton for Blisworth before 1725. If the Court Leet documents actually ceased in 1777 then perhaps so did the meetings - perhaps marking the end of cultivation by distributed lands. We have Church Vestry minutes from 1867 to 1895 and these minutes are almost completely devoid of any sort of 'business' items (until the planning of new sewers in 1890) so it is not possible to determine whether the Vestry took over the Court Leet function. In the Court Leet there was emphasis on the appointment of officers of the parish and nomination of constables, control of animal movements but very little was said about strip farming apart from indicating ~100 constables were involved in 1725 and 67 in 1777, an indication of lessening land area. One 1725 note is interesting; farmers were reminded to maintain their individual lower boundaries so that the mill brook may flow freely. Later years: There is evidence of an on-going transition from strip farming to a modern pattern but the picture is far from clear. Were the formal changes simply reflecting a trend, as sometimes suggested above, or were the changes forcing villagers to find other ways of providing food and/or income? There is little social commentary that could help answer the question. We have little information on mortality or on the flight of villagers to Northampton in this period. As sources of income before 1800 there was only agriculture and its infra-structural needs for the lowly educated, also for the wives, lace-making and being a servant or house-cleaner. For others there were trades, such as milling, carpentry and blacksmithing, and we have evidence of small shops and a few pubs - this mostly for the Victorian era. In the period after 1800 conditions were much better; there was the Canal and its wharf as a work place, there was the stone quarry from 1810, the railway works from 1835 and ironstone digging and working at the Hotel and gardens from 1850. As an example, in 1871, about 60 men worked as labourers for 9 farmers and 45 others were general labourers, some no doubt part-timing for farmers. Specialist skills, for men, included milling, quarrying and carpentry accounting for another 30 men while a host of other professions (butchery, railways, retail, teaching, post-working, clerical, blacksmithing, baking, coal delivery and baking) accounted for 70 more men. The removal of all common land rights in 1808 probably did not impact the village heavily, especially if a dispensation for firewood had been provided earlier; we do not know if it was. The Duke did however make one little concession - he converted about 10 acres at the Warren (Conygres Leys) into about 100 allotments of approximately 4 poles each (1 pole = 1/40 acre). The date of this action is not recorded, assumed between 1815 and 1839 (the later being the date of a Grafton survey that shows the established allotments). Interestingly, in 1838 the Royal Agricultural Society was formed, so maybe that was a stimulus or was the action simply an example of the Duke realising the consternation in the village in losing common land rights and asking for some suggestions on how he might help? A plausible alternative stimulus to the Duke may have been the controversy at the time of the "Swing Riots", calling for better conditions for mere labourers, which mostly occurred in the south - that was in 1830-1. Anyway, providing allotments was certainly not to compensate for the loss per se of common land strip farming. Of course, by 1860, the Duke's son did not worry too much about these allotments when the money for ironstone began to come in; about half of the allotments were ruinously converted to sub-soil by the crude methods used. There may have been a row over the mining but we have no Church Vestry records for that period. By the time of the formation of the Parish Council in 1894 the topic was evidently "old news" although the minutes were detailed. After 1800 and Field Names: As fields were subdivided by the farmers to conform to their land management requirements the names were gradually revised. There is a Duke's Agent's compact map, date estimated at 1825, at the NRO which gives all fields and minor subdivisions a 3 or 4 digit number, along with a name sometimes obscurely scribbled in pencil. The very small divisions such as used by Mary Jones c 1727 are all merged by 1825 into nearby larger fields - evidently the incomes of those households that used them have improved by 1825 and any ongoing demand for them was ignored. A portion of this map is shown here. It would be a major undertaking to recreate the map in a clear modern format. The 1825 map shows no common land at all. It does reveal maybe 50 acres of ex-woodland on the Plain that was held "in hand" pending clearance for arable cultivation. The Grafton Survey of 1839 lists just a few small fields with their tenants at the time but, for any field that is away from the village smallholdings and cottage assignments, there is no map to provide the precise location. Mona Clinch collected all names in the parish in 1935 and published a map in her little book about Blisworth. There is a review of Blisworth field names and their interpretations where possible. * this area is an estimate for 15C - 19C. Current area (2012) is 1881 acres. Milton took over four fields c. 1980 |