|

Study of Birth Records in Blisworth, 1550 - 1922

Tony

Marsh

Text Processing: Perl is ideally suited to the manipulation of text. It is

capable of detecting 's' (ie. son) or 'd' (ie. daughter) in a variety of

syntaxes and also detecting any double occurrence of the word 'of ' in a

syntax such as "s of

Charles & Harriet of Wolverton" and so give an opportunity to

exclude visiting parents. Other

phrases such as "base born" and "bastard" allow a

logging of most baptisms of illegitimate children. In the original Excel

file, once filtered for baptisms, there were 4934 valid entries and a

justification for excluding 507 of them for a variety of reasons. A

total of 247 entries were for visiting parents, incl. 3 adults, and so

were ignored. They displayed an SRB ratio of 1.05, as a sub-group,

and the importance of this is discussed later. There were 260 blank or

seriously uninformative entries. The great majority of these (93%) were

created in the interval 1550 to 1650. A closer examination was made of

these, looking for mention of a given name so that entries could be

classified for gender and this was possible for 87 entries. However,

some may have corresponded to adults, possibly already baptised without

their knowledge. For this reason this small group was finally omitted. A

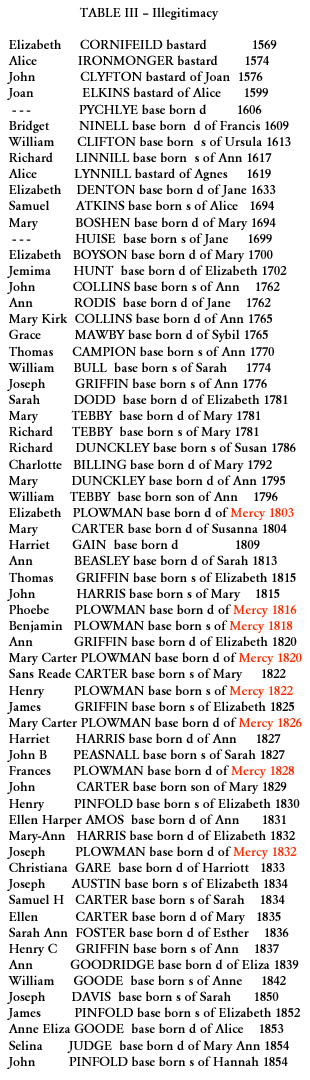

total of 64 illegitimate children were logged from 1550 – 1922 and the

total was later adjusted for a reason that will become clear.

Remarkably,

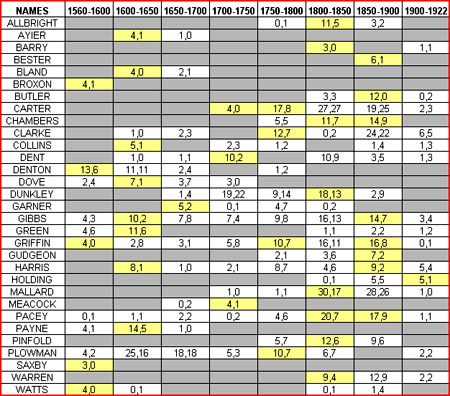

only 31 family names sported a strong male bias at some stage (and

rarely twice, interestingly). Such situations are highlighted in yellow

while the relatively un-biassed periods for the families are shown with

a white background. At each point the format of the entry is “boys

comma girls”. A grey background is used where there are no births for

a family within a particular 50-year period. This distinction, with grey,

probably shows when a family has departed or just arrived in the

village. A few families, eg. the

Paceys, Gibbs and the Griffins, have occupied the village continuously

from 1550 -1922 (but mysteriously have all now departed).

The Carters began in the early 1700s and are still going strong

today. Families that appear over two separate periods are presumed to be

not closely related branches and have the same surname more-or-less by

coincidence - eg. the Greens and the Watts. Before attempting to give any account of the

results it is sometimes helpful in the massaging of complex data to

extract what, to the scientist and engineer, is known as any dimensionless group. This promotes the suggestion of mathematical

relationships between elements of the data. The SRB is already

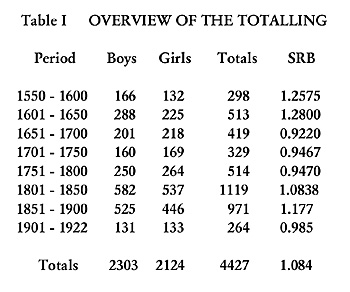

dimensionless, being a ratio without units. The data in Tables I

and II could be combined as follows. One could note the count of

male bias incidence with each 50-year period and compare that to the

total number of baptisms for the same period. Thus,

as an example, the number of incidents in the 1750-1800 date range is 4.

We set that as (4 +/- 1) and divide it by the level of birth activity in

that period, which was 514 according to Table I. A "families

per 100 births" index so formed is thus: Fam/100

index for (1750-1800) =

(4 +/- 1) divided by 5.14 =

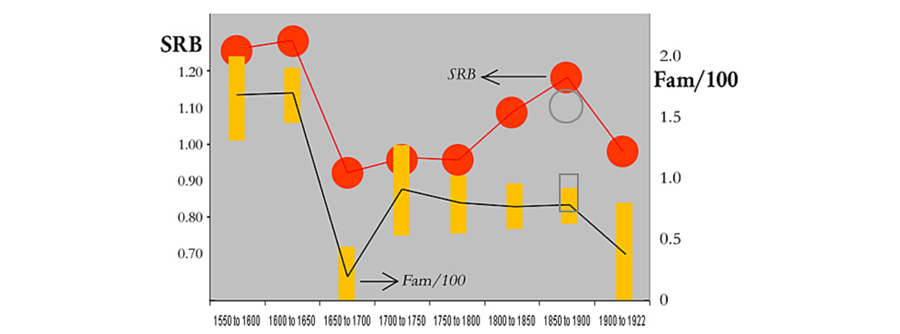

0.6 to 1.0 The justification for the +/- 1 is that the measure of “actual male bias” is subjective and liable to error. The index is dimensionless because it is the quotient of two plain numbers. In the diagram below, Figure 1, there is plotted against the date ranges both the SRB ratio and the Fam/100 index.

By

inspection, there appears to be a correlation between these two factors

in that between 1550 and 1800 the two trends follow each other. To

confirm this impression just imagine the data for SRB being drawn

lower down on the graph compared to where it is (ie. move by minus 0.1

on the SRB scale). The SRB =

0 point, which is meaningless, is suppressed anyway. We see that,

after 1800, the SRB takes off upwards and "peaks",

compared to an expectation based on the Fam/100 index, at around

the middle of the 1850-1900 date range. Before considering the conditions regarding births in the two date ranges, before 1800 and after 1800, it will be useful to be clear on definitions. These data are about baptisms and not strictly about births. There are at least three distinguishable cases where the difference is very important. (i). A

mother may (a) conceal her pregnancy, (b) have her baby in private and

alone and (c) not tell anyone about its subsequent death. This would

have been common temptation for un-married young girls with all to loose

because of the stigma. Up to about 1700 the law was clear on this issue

and if the woman were found guilty on all three counts the sentence was

a capital one, for what was termed “infanticide”. Some sympathy was

being introduced in the 1600s and by 1800 the situation had become one

of laissez faire from a legal standpoint. (ii). A

situation where a birth is not necessarily reported and the baby dies

very young (at less than 6 years) has always been regarded with sympathy

even though the cause of death might have been unnatural or partly

brought on by the mal-nutrition of a very sickly child. There is no term

for this type of loss in the literature so here it is given the label

“family wasting”. (iii).

Cases as in (ii) where the death is not reported –

“unrecorded family wasting”. It is recommended that one should read Appendix

4 that deals with this topic. Discussion Pre-1800

era:

Blisworth was essentially a small agricultural community. Social

standards were established and maintained by the Lord of the Manor

(being an agent of the King until ~1700), by the Rector and by some of

the parish officials such as the Constable and the Overseer of the Poor.

It seems inconceivable that much distortion of the records occurred due

to infanticide, ie. (i) above. One only needs to inspect the low

level of illegitimacy to feel convinced of this. Possibly there may have

been a fair amount of unrecorded family wasting. The abstract for a

treatise was found in the searches (see the Appendix I) that dealt

with practices common in a German parish where arguments for reducing

the count of girls was justified as the natural loss of young boys was

always a major concern. (The loss of more boys than girls was recorded

also in Blisworth). The high value of the SRB may be partly for

reasons of unrecorded family wasting but probably only partly. A more likely

contributory factor is the light level of inter-breeding within the

community that would persist even though some males were encouraged to

find their wives in the neighbouring villages. It was frequently the

case that two families got on so well together that brothers married

corresponding sisters. Subsequently the offspring would be genetically

very close cousins, all the more confusing if three or four families

were involved. Occasionally these cousins would carelessly marry and

affect the genes. Alternatively, would

the stress from the pre-Civil War years have fired up an extra male

bias? We know little of the society of that time. We know of only one fellow who departed the village for a few

years and joined the Roundheads. He was Richard

Bland, the second eldest

one of four sons (no daughters!) that were born from 1623 to 1632. He

survived all the battles and returned with, eventually, a good pay that

would have exceeded earnings possible in agriculture. Having three

competing brothers perhaps had encouraged him to seek his fortune

elsewhere. Could these conditions have

encouraged a common male bias? The opinion of a geneticist is required.

In the

time interval of 70 years there was no longer a scarcity of new

employment, or so it seemed, but the influx of newcomers to the village

virtually doubled the population and doubled the birth rate. One can

imagine a majority of society that was poor or in poverty looking on at

the good fortune of a few lucky entrepreneurial people. The loss of

a moral compass, hitherto set by a Rector and a few influential people,

one supposes gave the community a sort of “go ahead”. The scale of illegitimacy

took off and there was perhaps an enormous increase in male-male

competition. The illegitimacy rate of 2 in 25 years that had been

maintained for at least 200 years climbed to a level of nearly one per

year. The claimed large

flush of them at the time of the

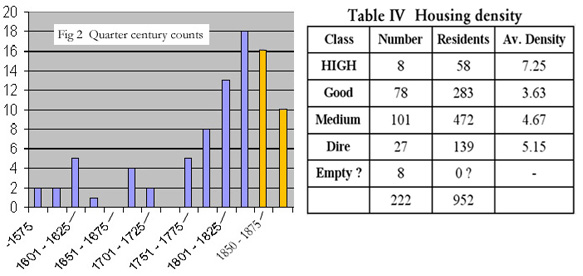

canal building (1795 - 1810) was not noted in fact. The bar chart below,

Figure 2, condenses the table opposite. Oddly, from 1854,

there were no more illegitimacies recorded in the usual way. This was

because of the move by Rev Barry to follow the CoE

"high-church" fashion causing him to simply ban any use of the

phrase "base born" from 1854. The chart is therefore continued

with a different colour showing babies baptised with just a mother

present. Maybe his ministry improved societal standards after ~1850

because the chart does show a decline. Another factor was the new 1872

law that made the father equally liable for the support of the

illegitimate child and, incidentally called for the compulsory recording

of all births. Rather amusing is

the performance of Miss Mercy Plowman who simply could hardly stop

having children out of wedlock (8 in all, see red highlights, her last

at the age of 51). Some of her babies appear to have been fostered by

the Carter family where she was lodging in 1871. Five other families

besides Plowman achieved multiple illegitimacies. All this expansion

created over-crowding. The railway company in circa 1850 built the

twelve houses near the railway arch for their workers who were enjoying

a fair to good income. There were 11 houses built ~1870 to

a “Grafton design” that were intended for prosperous families. The baker R. Westley,

however, built two blocks of tenements containing 28 poorly

specified units for the poorer families in 1855 and also a few cottages

for higher grade workers at

Pynus in ~1890. The poor had the new tenement and and were crowded into

them and the lower grade cottages, some of which were subdivided into 3

or 4 units. Grafton, the owner of Blisworth till 1919, was

criticised in parliament in

1911 for his derisory record in house

building and it was not until the Towcester Rural District Council began

razing old houses, in the name of public health, in the 1930s, building

over 36 new Council houses, that the village could be said to be

catching up on the population expansion. Crowding was pretty bad. The 1871 census

demonstrates this and shows 952 people resident in 222 dwellings. The

distribution of housing density has been determined from a knowledge of

the size of the dwellings and the houses were divided into “classes”

as HIGH, Good, Medium or Dire (or evidently Empty or "residents not

at home"), see Table IV below. Among the

"Medium class" and those described as "Dire" there

were 25 dwellings with 6 or more occupants, up to a total of 10. The

high apparent occupancy for the houses classed as "HIGH" is

due to the fact that they included servants and a total number of

bedrooms of around 6. Most of the units considered "Medium or

Dire" comprised one bedroom, one shared living room, a shared

kitchen area and maybe a shared "copper" for hot water (no

bathroom, water from a well nearby). With that there would often be an

outside closet toilet, emptied manually twice weekly, shared between 4

to 6 households. Fresh tap-water and flush toilets arrived in the

village in 1953 - 17 years after Northampton. Within a population

sub-group of about 400, this would certainly be an environment capable

of harbouring infant ill health with a prospect of infanticide or

unrecorded family wasting. Indeed,

after nearly 100 years of grossly unhygienic use, it was perfectly

reasonable for the Council to raze such “in-grained” houses and

start again (though villagers with ideas of property development found

the action of “replacing stone with utility brick” lamentable). The SRB ratio

just before 1800 was hovering in a slight female-bias state, ie. SRB

~ 0.95, and this could have been because there was an under-current of

male babies dying before they could be baptised. Quite why this ratio

was overturned into a male-bias in the Victorian years is something of a

mystery. Could there be a similar but diluted effect from male-male

competition (compared to the 1600s) arising in the genetics of the

community? At least comforting is the fact that from 1800 any suspicion

of inter-breeding would be dispelled.

It

is a fact that the SRB ratio for the Victorian period is anomalously

high and demands to be explained. We have discussed crowding and poverty

which were both undeniable factors influencing society in the Victorian era

and alluded to a loss of moral compass (as against the standards at that

time, it must be emphasised). Perhaps a level of unrecorded

family wasting was the reason for a high SRB which basically is pointing

to a moderate shortage of recorded female births. Incidently there is a

study of the effects of poverty in a large Venzuelan population

(catholic, probably mostly healthy 'moral compass') and there the SRB

remained in the range 0.98 to 1.08 while correlations implying

poverty-driven family size control were found. So this is the

justification here of "adjusting" the statistics for Victorian

Blisworth. If an arbitrary

total of 106 infants as unrecorded family wasting (in 50 years)

were to be added to the 71 infants statistic and notionally counted as

births then, with a reasonable excess of girls over boys assumed in the

wasting, the entered points in Figure 1 above, for the 1850 –

1900 period, would occupy the grey outlined positions shown there, with

an SRB of 1.10. The change provides some improved conformity

between the two plots but that is rather modest compared with an

adjustment one would expect, naively, from a simple set of ideas. At

least it is evident that an incidence of wasting may make an adjustment in

the right direction but the level of wasting at 106 seems too high to be

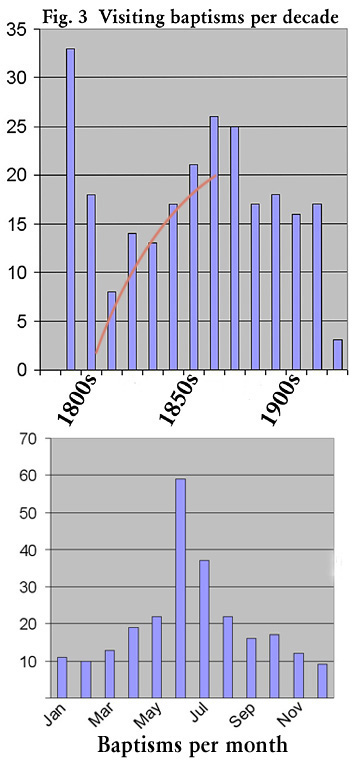

reasonable. Visitor Baptisms: This is a rather strange topic and, at first sight, merely an unimportant side issue. Figure 3 shows the number of such baptisms by decade. There were only three cases before 1780 and so it is only necessary to cover the period from 1780 to 1930 (the records cease in 1922). The high level in the 1790s and the 1800s could be explained by a large number of temporary visitors, as families, to the village for the canal and tunnel construction. The tiny component for the 1920s was due to WWI and only three years being represented.

Conclusions (1).

Whilst life in Blisworth did not equate to city life, it

is important to not have an overly romantic view. There was, for a

while, a context for Blisworth that resembled a city environment and the

new elements of industrialisation, namely transportation and quarrying,

had created such environment exacerbated by a level of social laxity and, for

some of the population, poverty and

over-crowding. (2).

The incidence of unrecorded wasting is not a proven fact for the

Victorian period in Blisworth but the evidence is disconcerting.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Appendices

Various appendices

are attached. Appendix 1 refers to a treatise on the practices in

a German parish. Appendix 2 presents an extract of another book

that discusses infanticide. Appendix 3 covers the Victorian

inclination to use laudanum-containing preparations to quieten children

– this, one can imagine, would be very tempting in order to

successfully use the single bedroom. The danger from it is that too much

laudanum (morphine) might be used and the child looses appetite and

energy and may eventually die addicted. A Pharmacy Act in 1868 demanded

that “Poison” be displayed and directed that pharmacies and not

grocers would sell in future. A survey of the local newspaper, the

Northampton Mercury, was made for the period 1860 to 1863 and the

presentation of adverts on various narcotic syrups or pills was easy to

find. For example, Dicey’s Bateman Pectoral Drops is a morphine

containing cough remedy, as is Lambert’s Asthmatic Balsam.

Interestingly, Dicey, as the owner of the newspaper, was subscribing to

a marketing deal with Bateman and a “quack-doctor” website, see

below, comments that the morphine content varies widely, deal to deal.

Appendix 1: Human sex-ratio manipulation: Historical data from a German parish

Eckart Voland On the basis of demographic data of a parish in Schleswig-Holstein,

characterized by a by this intervention, ie. as a result of less well being taken care

of. This resulted in

(1) inheritance practices favouring male descendants, and (2) the proportion of marriage perspectives for the

sons

as opposed to the daughters being in favour of the boys,

in contrast to other social classes. The classes of the parish without land property revealed a different

pattern of Appendix 2:

Sex Differentials in

Survivorship and the Customary Treatment of Infants and Children Lauris

McKee Infanticide

is a direct and violent means of removing children from a population.

For this reason, it has attracted public concern and occasioned careful

scientific inquiry. Parents

generally are deeply, emotionally invested in their children.

Institutionalised practices prejudicing child survival have the

advantage of interposing time and space between a treatment that

enhances the probability of early death, and a child's actual death.

Hence, the relationship between cause and effect can pass unperceived.

For example, infection of a ritually-inflicted wound appears several

days after the injury is incurred. In societies with no germ theory of

disease, pathogenesis would not be attributed to un-sterile conditions

but to other factors, such as imperfect performance of the ritual act or

the malfeasance of witches or supernatural. Scrimshaw (1982) notes that

seeking psychological distance through temporal and spatial distance

figures even among infanticidal parents who often abandon rather than

directly murder their children. In this chapter, the major goal is to convince

the reader that infanticide exists, and to argue that two of its

potentially numerous functions arc (1) the limitation of population

growth; and (2) the management of demographic structure by control of

the sex ratio. The latter, it is suggested, results in selective female

infanticide to compensate for universally higher male mortality in

infancy and childhood, and may be implicated in the prevalence of

systems of male preference.

Appendix 3:

Endangered

Lives: Public Health in Victorian Britain. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1983.

pp. 34-35 Wohl,

Anthony S. Medical officers were convinced that one of the major causes of

infant mortality was the widespread practice of giving children

narcotics, especially opium, to quieten them. At Id an ounce laudanum

was cheap enough — about the price of a pint of beer — and its sale

was totally unregulated until late in the century. The use of opium was

widespread both in town and country. In Manchester, according to one

account, five out of six working-class families used it habitually. One

Manchester druggist admitted selling a half-gallon of Godfrey's Cordial

(the most popular mixture, it contained opium, treacle, water, and

spices) and between five and six gallons of what was euphemistically

called "quietness" every week. In Nottingham one member of the

Town Council, a druggist, sold four hundred gallons of laudanum

annually. At mid-century there were at least ten proprietary brands,

with Godfrey's Cordial, Steedman’s Powder, and the grandly

named Atkinson's Royal Infants Preservative among the most popular. In

East Anglia opium in pills and penny sticks was widely sold and opium

taking was described as a way of life there. Throughout the Fens it was

used in 'poppy tea,' and doctors there reported how the infants were

wasted from it — 'shrank up into little old men', 'wizened like little

monkeys' is the way they were described. Opium killed far more infants through starvation than directly

through overdose. Dr. Greenhow, investigating for the Privy Council,

noted how children 'kept in a state of continued narcotism will be

thereby disinclined for food, and be but imperfectly nourished. Marasmus,

or inanitition, and death from severe malnutrition would result, but the

coroner was likely to record the death as 'debility from birth,' or

'lack of breast milk,' or simply 'starvation.'

Appendix 4: Background material

Infanticide: a case study by Richard Brown (from

his website blog) In West London, on the evening of 1 September 1856, a grisly

discovery was made. The bodies of newborn twins were found wrapped in a

bloodstained petticoat and chemise in the front garden of a house at

Pentridge Villas, Notting Hill. Mr Guazzaroni, the surgeon who conducted

the post-mortem at the Kensington workhouse, found that the twins had

died because of intentional suffocation and exposure. A verdict of

wilful murder by persons unknown was returned at the coroner’s inquest

but the twin’s mother was never traced. Infanticide was disturbingly

common in Victorian Britain.[1] Lionel Rose estimates that of 113,000

deaths of children under the age of one in 1864, 1,730 were due to

‘violence’ with only 192 of those being classified as homicides.

Contemporaries maintained that Britain was suffering from an epidemic of

child-killing blamed on ‘puerperal insanity’, a form of post-natal

mania that accounted for as much as 15% of female asylum admissions in

some years. [2] From the early 1840s, questions were being openly asked on the floor

of the House of Commons where Thomas Wakley, coroner, surgeon and MP

shocked his audience by claiming that infanticide[3], ‘was going on to

a frightful, to an enormous, a perfectly incredible extent.’[4]By the

1860s, the problem was believed to have reached crisis proportions and

figured as one of the great plagues of society, alongside prostitution,

drunkenness and gambling. According to some experts, it was impossible

to escape from the sight of dead infants’ corpses, especially in the

capital, for they were to be found everywhere from interiors to

exteriors, from bedrooms to train compartments. One observer commented

that bundles are left lying about in the streets... the metropolitan

canal boats are impeded, as they are tracked along by the number of

drowned infants with which they come in contact, and the land is

becoming defiled by the blood of her innocents. We are told by Dr

Lankester that there are 12,000 women in London to whom the crime of

child murder may be attributed. In other words, that one in every thirty

women (I presume between fifteen and forty-five) is a murderess.[5] Even The Times was forced to concede at the end of a long

list of Herod-like statistics on the subject that ‘infancy in London

has to creep into life in the midst of foes’.[6] At every new

‘epidemic’ of dead babies found abandoned on the streets of the

capital, there was a public outcry focussed on society’s responses. In

1870, in London, 276 infants were found dead in the streets and in 1895,

this figure reached 231. For the Ladies’ Sanitary Association,

civilisation itself was under threat: ...an annual slaughter of innocents takes place in this gifted land

of ours... we must grapple with this evil, and that speedily, if we

would not merit the reproach of admitting infanticide as an institution

into our social system.[7] Many of the women involved were from the lower classes and many of

the babies were illegitimate. However, pleading this form of temporary

insanity when taken to court was frequently met with a sympathetic

response from judges, despite the obvious suspicion that some cases were

murders. The problem of infanticide was brought into strong focus by the

case of Mary Newell.[8] Born in south Oxfordshire, Mary had been a

servant since she was 16. Without work in the summer of 1857, aged 21,

she travelled to Reading where she met as old acquaintance, poulterer

William Francis who invited her for a drink at his house. Mary ended up

pregnant and Francis showed no further interest in her. Although she

soon found employment within two months she left and single, pregnant

and unemployed and having failed to persuade Francis to marry her, she

was admitted to Henley workhouse on 11 January 1858. In May she gave

birth to a son, Richard and remained at the workhouse until August when

she walked the eight miles to Reading to seek help from Francis who

refused. Unclear what to do and confused, Mary wandered round all night

and eventually she undressed her baby son, laid him by the bank of the

Thames and let him roll in. At Mary’s trial, there was outrage at Francis’ attitude, as it

was believed that had he shown any willingness to help, the baby would

not have died. Although he admitted his neglect at the trial, this did

little to moderate local feeling and after the verdict he was attacked

by a mob, beaten and left semi-naked, an event repeated when news of the

trial’s outcome reached his new home at Wallingford. Mary was

condemned to death but was in such a state that she was committed to the

local asylum. A petition was launched asking Queen Victoria to commute

her sentence and the local mayor, magistrates and nearly 800 others

signed it. A deputation of people from Reading visited the Home Office

to lobby and this intervention appears to have saved Mary’s life. Infanticide was an act of murder and as such, the guilty parties

could be exposed to the full force of the law. Yet, on this politically

delicate question, sentencing by the courts depended as much on the

facts as on the medical interpretation placed on them. Victorian

leniency towards infanticide was shaken in 1865 when a woman from

London, Esther Lack, killed her three children by slitting their

throats. After the court backed an insanity plea, one newspaper openly

questioned the willingness of courts to find in favour of such

defendants. Evidence from London shows that most women charged with

infanticide between 1837 and 1913 were in their early to mid-20s though

some were as young as 16 and that the younger the woman, the more likely

she was to be acquitted or guilty only of the lesser offence of

concealing a birth. However, it was not until the 1922 Infanticide Act

that the death penalty was abolished for women who murdered their

newborn babies if is could be shown that the woman in question had had

her balance of mind disturbed as a direct result of giving birth. The advent of the life insurance business brought a further motive

for murder but in particular infanticide. Arsenic poisoning was

difficult to identify since its symptoms were similar to those of

dysentary, gastritis and other causes of natural death and magistrates

were generally unwilling to squander public funds while the chances of

detection were so small.[9] Families could enrol their children in a

‘burial club’ for a halfpenny a week and when the child died the

club would pay out as much as £5 towards funeral expenses. Since a

cheap funeral cost around £1, this left a valuable surplus for feeding

the remaining children and some families enrolled each child in several

clubs to increase the payout. There was a saying in Manchester, though

it existed across the country that a burial-club baby was unlikely to

survive for long. The burial-club scandal became so widespread that

legislation was passed in 1850 prohibiting insuring children under 10

for more than £3. However, the lure of life insurance remained a potent

cause of infanticide. Mary Ann Cotton, a former school teacher from

County Durham murdered most of her 15 children and step-children, as

well as her mother, three husbands and her lodger, before she was hanged

in 1873. The harshest decisions were certainly those meted out to the

professional baby farmer found guilty of infanticide. One of the first

and most sensational trials was that of Margaret Waters, the so-called

‘Brixton Baby Farmer’ in 1870, who was found guilty of conspiracy to

obtain money by fraud and the murder of a baby.[10] She was executed

amid extensive popular agitation and press coverage. In a sense the

pattern had been set and when, in 1879, Annie Took was similarly found

guilty of smothering and dismembering an illegitimate physically

handicapped child she had been paid £12 to look after, she too was

executed. Other high-profile baby farmers such as the Edinburgh

murderess Jessie King in 1887[11] and Amelia Dyer[12] suffered a similar

fate. Yet not all of these criminals were sentenced to death and other

cases that received front-page coverage such as those of Catherine

Barnes and Charlotte Winsor resulted in verdicts of life imprisonment. There was a growing body of evidence by the 1870s that infanticide

was a crime committed primarily by women and, more often than not, by

the mothers or the surrogate mothers of the infants themselves.

Undoubtedly, the more ‘acceptable’ of these two explanations was the

latter, that these crimes were the work of depraved, unscrupulous women

who had lost all sense of their maternal instincts and indulged in a

commercial trade with life itself inside a profession known popularly as

‘baby farming’.[13] The term first appeared in The Times in

the late 1860s, and, according to one medical practitioner of the

period, was coined ‘to indicate the occupation of those who receive

infants to nurse or rear by hand for a payment in money, either made

periodically (as weekly or monthly) or in one sum’.[14] It was

regarded with a great deal of suspicion in many quarters, as an

“occupation which shuns the light”[15] and not simply a primitive

form of child-care. However, its popular appeal and social function were

immense at a time when illegitimacy was stigmatised and single mothers

excluded from the most elementary means of supporting their child. By the latter part of the nineteenth century, the mechanics of the

system had become well established. The ‘baby farmer’ was usually a

woman of a mature age and poor working-class background who would offer

either to look after the ‘unwanted’ child or ensure that it was

‘passed on’ to suitable adoptive parents. The fee for this

transaction varied according to the specifics of the contract but was

usually situated between £7 and £30.[16] In the majority of cases

there was also a tacit understanding between the two parties that, in

the harsh conditions of life in working-class areas of the nation’s

cities, the child’s chances of survival would be extremely slim. What

particularly outraged public feeling was that this trade had a visible,

almost respectable, side to it for it was practised openly through

advertising, in national, regional and local newspapers. Not

surprisingly under such circumstances, the financial considerations

involved in this extensive traffic in infant life gradually became the

focus of deep suspicion. For the British Medical Journal of 1868,

these ‘baby farmers’ would not have the slightest difficulty in

disposing of any number of children, so that they may give no further

trouble, and never be heard of, at £10 a head.[17] Baby farms were denounced as nothing more than ‘centres of

infanticide’, a convenient way for women to solve the problem of

unwanted and illegitimate births. It was, for instance, widely believed

that these babies were often left to wilt away and die, sometimes helped

along with a little soother known as ‘Kindness’. These rumours found

credence in the fact that at this time it was common practice, not only

among those whose looked after children, but also among mothers

themselves, to use a certain ‘Godfrey’s Cordial’ to quieten the

babies, and that this, if dosed incorrectly, could lead to ‘the sleep

of death’.[18] Little however was known about the role of the mothers in this

trade. The Times had no doubts that the women who sent their

children to baby farmers were ‘complicitous and selfish’ and

not naive and impoverished victims in their own right.[19] Yet a survey

of those implicated in the more spectacular trials of the period

suggests that most were guilty only of the crime of having a child

outside of wedlock. Crime reports invariably refer to the biological

mothers’ occupation as that of bar-maid, prostitute, factory or mill

worker, domestic servant. Much more rarely are there references to

‘outraged’ middle-class girls and unfaithful upper-class women

having recourse to the infamous baby farmers. In the Margaret Waters

case, for instance, the court heard of 17-year-old Jeanette Cowen, who

had been raped by the husband of a friend and, on the birth of her son,

her father arranged ‘adoption’ procedures with Waters without the

mother’s consent. Evelina Marmon, a barmaid from Bristol,

confided her 10-month-old child to the safe keeping of Amelia Dyer

because she was temporarily unable to look after it. She was unaware

that the baby had been strangled and disposed of until the trial, as

Dyer sent her regular reports about its progress. The illegitimate child

of Elizabeth Campbell, who died in childbirth, was ‘adopted’ for a

generous fee by Jessie King to avoid a family scandal but nobody

apparently suspected that any harm would befall the child. The problem of ‘baby farming’ proved intractable, despite the

sustained pressure of such groups as the Infant Life Protection

Society that called for the registration and control of all people

in charge of babies on a professional basis.[20] Not only was this

activity an integral part of the social regulation of the nation’s

sexuality, it also fulfilled a valuable economic role by allowing

working-class women to occupy paid employment. Government interference

in such a private sphere was therefore problematic in the extreme. The

breakthrough only came through a private member’s initiative which

became the Infant Life Protection Act in 1872. This reform made

registration obligatory with the local authority for any person taking

in two or more infants under one year of age for a period greater than

24 hours. Furthermore, deaths of infants in such care had to be

communicated to the Coroner within 24 hours. It was a timid start since

the scope of people exempted from the Act was significant; relatives,

day-nurses, hospitals and even foster women were all excluded and no

‘authentification’ of contracts between parent and baby farmer was

required. Moreover since the registration of all births, live and dead

did not become compulsory until 1874, unless the authorities actually

knew that a baby had been born, it was possible for it to die, be killed

or be disposed of without anyone even noticing its existence. Only after

other sensational ‘epidemics’ of infanticide in the ensuing years

did a further Infant Life Protection Act force its way through

Parliament in 1897. This Act finally empowered local authorities to

control the registration of “nurses” responsible for more than one

infant under the age of five for a period longer than 48 hours.[21] NOTES [1] Rose, Lionel, Massacre of the Innocents: Infanticide in

Britain 1800-1939, (Routledge), 1986 and more generally Jackson,

Mark, (ed.), Infanticide: Historical Perspectives on Child Murder and

Concealment, (Ashgate), 2002, Thorn, Jennifer, (ed.), Writing

British infanticide: child-murder, gender, and print, 1722-1859,

(University of Delaware Press), 2003 and McDonagh, Josephine, Child

Murder & British Culture, 1720-1900, (Cambridge University

Press), 2003, pp. 97-183. [2] Puerperal psychosis is now a well-recognised event, affecting

perhaps one in every 500 births in the UK. It normally happens in the

first month of the new child’s life and takes the form of a severe

episode of mania similar to that suffered by manic depressives. Patients

may become confused and delusional, and in the most extreme cases try to

harm themselves or their new child. See, Marland, Hilary, ‘Getting

away with murder? Puerperal insanity, infanticide and the defence

plea’, in ibid, Jackson, Mark (ed.), Infanticide: historical

perspectives on child murder and concealment, 1550-2000, pp. 168-192

and ‘Disappointment and desolation: women, doctors and interpretations

of puerperal insanity in the nineteenth century’, History of

Psychiatry, Vol. 14, (2003), pp. 303-320. [3] William Ryan described infanticide as ‘the murder of a

new-born child’ although there is no specific time applied to the term

‘new-born’; it is not restricted to days after the birth. Ryan,

William Burke, Infanticide: Its Law, Prevalence, Prevention and

History, (J. Churchill, New Burlington Street), p. 3 [4]Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates, 3rd Series,

76, 1844, col. 430-431. [5] Ibid, Ryan, William Burke, Infanticide: Its Law, Prevalence,

Prevention and History, pp. 45-46. [6]The Times, 29 April 1862. [7]

Baines, Mrs M.A., Excessive Infant Mortality: How can it be

stayed?, (J. Churchill and. Sons), 1865. [8] National Archives: PCOM 4/36/37 and the review of Ryan, William

Burke, ‘Infanticide: its Law, Prevalence, Prevention and History’, The

British and Foreign Medico-Chirurgical Review or Quarterly Journal of

Practical Medicine and Surgery, Vol. xxxi, (1863), pp. 1-27. [9] See, Whorton, James C., The Arsenic Century: How Victorian

Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work and Play, (Oxford University

Press), 2010, pp. 27-33. [10] On Margaret Waters’ case, see HO 12 193/92230 [11] One of the children in her care apparently died from an

overdose of whisky. King was executed on 11 March 1889 in Calton Prison,

and had the unenviable distinction of being the last but one woman to be

hanged for murder in Scotland. [12] Dyer’s reputation as a mass-murderess stems from her modus

operandi for after strangling her victim with tape, she placed it in a

carpet bag (nicknamed the ‘travelling coffin’) and threw it into the

Thames. She stated in her confession ‘You’ll know all mine by the

tape around their necks’. Fifty-seven-year-old Dyer was

responsible for at least 17 deaths before her arrest in 1896. For a

detailed police report, her trial and sentencing, forensic detail,

incriminating evidence as well as her written confession, see Thames

Valley Police Archives. See also, Vale, Alison, Amelia Dyer,

angel maker: the woman who murdered babies for money, (Andre

Deutsch), 2007. [13] See, Behlmer, George K., Child abuse and moral reform in

England 1870-1908, (Oxford University Press), 1982, pp. 25-42,

150-156 and 211-221. [14]Curgenven,

J.B., On Baby-farming and the Registration of

Nurses, Read at a meeting of the Health Department of the

National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, March 15,

1869, (National Association for the Promotion of Social Science),

1869, p. 3. See also, Greenwood, James, The Seven Curses of London,

(S. Rivers), 1869, pp. 29-57. [15]North British Daily Mail, 2March 1871. [16] Ibid, Rose, Lionel, Massacre of the Innocents. Infanticide

in Great Britain 1800-1939, p. 94. [17]Cit,

Altick, Richard D., Victorian Studies in Scarlet,

(W.W. Norton & Co.), 1970, p. 285 [18] See, Findlay, Rosie, ‘‘More Deadly Than The Male’...?

Mothers and Infanticide In Nineteenth Century Britain’, Cycnos,

Vol. 23, (2), (2006), URL: http://revel.unice.fr/cycnos/document.html?id=763

[19]The Times, 4 July and 24 September 1870. [20]The Infant Life Protection Society, created in 1870 and

the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children

established in 1889 campaigned relentlessly for the introduction of

better ‘policing’ of working-class families: Allen, Anne and Morton,

Arthur, This is your child: the story of the National Society for the

Prevention of Cruelty to Children, (Routledge & K. Paul), 1961,

pp. 15-33. They recommended more foundling hospitals to be set up as

well as public nurseries for the children of the poor, as they believed

that working-class mothers’ lack of education and standard of living

both conspired against infant life. See, Arnot, Margaret L., ‘Infant

death, child care and the state: the baby farming scandal and the first

infant life protection legislation of 1872’, Continuity and Change,

Vol. 9, (2), 1994, p. 290 and ‘An English Crèche’, The

Times, 8 April 1868. [21] The Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act was passed in 1889 to

protect children under the age of fourteen from ill-treatment. Although

in 1881 the Midwives Institute was founded, it took almost another

twenty years before the first Midwives Act was passed in 1902; the

Central Midwives Board were to govern training and practice of midwives

in England and Wales, and it was illegal to practise without

qualification (Scotland 1915 and Northern Ireland 1922). Appendix

5: The Excel and Perl process.

MSExcel

Set in date order and filter for baptisms only

MSExcel

Then, alphabetically sort the surnames

MSExcel

Save as a new file in "comma separated variables"

format (ie. plain text)

Perl Run

this routine for each new text line

Perl cont..

Split the fields at the commas.

The rest of the routine works on the “Information field”

Detect and exclude "visitor parents" for separate

listing

“Surname field” - Take surname and either continue

totalling, if the surname is the same as

Detect uninformative entry, exclude and set for separate listing

Detect "s" for boy, "d" for daughter and then

increment count against surname

Detect "bastard" & "base born" and copy

for listing

Perl

On “End of file” close lists of visitors, uninformative,

bastards and surnames |

We should however look closely at the

possibility of either infanticide or unrecorded family wasting being

embedded in the figures. The 1871 census was used to analyse this issue

along with the processed data for the 50-year period, 1850 – 1900. In

that period there were 71 recorded deaths at an age less than 12 months

and a further 74 for children under the age of 6 years. These two

figures amount to a loss of 27% of all births (baptisms) and there were

in fact 38% more recorded boy deaths than girls.

We should however look closely at the

possibility of either infanticide or unrecorded family wasting being

embedded in the figures. The 1871 census was used to analyse this issue

along with the processed data for the 50-year period, 1850 – 1900. In

that period there were 71 recorded deaths at an age less than 12 months

and a further 74 for children under the age of 6 years. These two

figures amount to a loss of 27% of all births (baptisms) and there were

in fact 38% more recorded boy deaths than girls.