BLISWORTH

Sewage Schemes and Water

Supplies, 1890 - 1960

Sewage Schemes

The story of the troubles experienced by

the village from their sewage system is one of striving to keep up with the

rapid expansion of the population and laying on an improved service as befits the

20th Century.

The oldest reference to sewage in

Blisworth is a scrap of paper, held at the NRO, on which two sets of notes describe tenders by Mr

Ratledge and Mr Sturgess for repairing piping and cesspits distributed around

the village. The date was 1890. Both refer to about 1100 yards of piping (various diameters)

and either 12 or 14 cesspits. It is not clear whether the pipes were new or

replacements were being quoted for. Costs quoted were around £100.

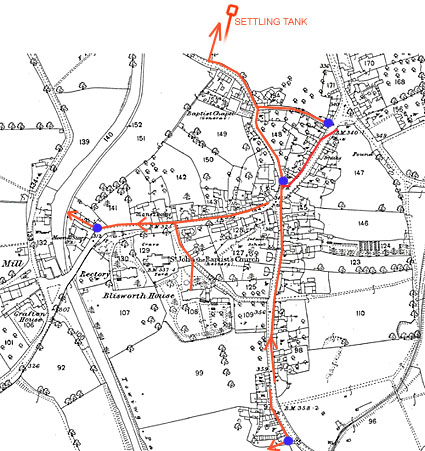

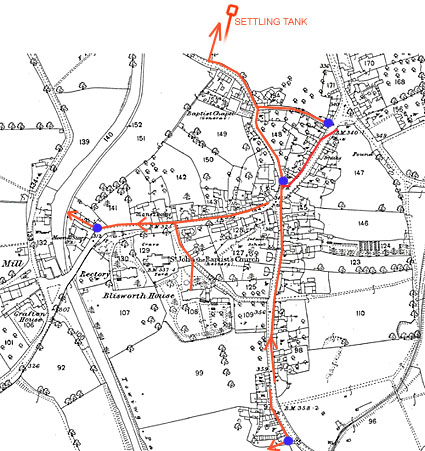

Another item held in the 35P/C section includes maps of the sewer pipes from

which the diagram below has been assembled.

The arrangement was that nearly all houses

either had their own privy, or a share of one, the bucket within which was periodically emptied

either onto the gardens, into a nearby cesspit or into one's 'dedicated' drain

extension if the house or yard was lucky enough to have one. Cesspits are

marked as blue dots and it is amusing to observe that two of them were located

very near to a public house. Drain extensions would have had an iron lid to

keep smells down. Incidently, if this website stands a

good chance of surviving 50 years, there will be nobody to define 'privy'.

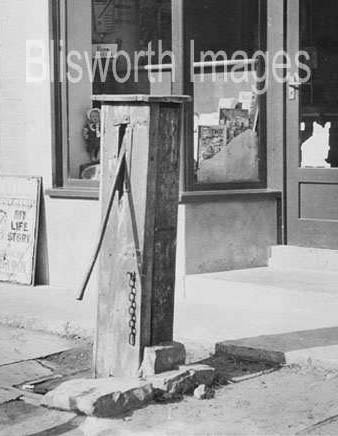

The attached pictures are therefore provided to place

on record the grim, cold and roughly-shod sheds, set at some distance from the

house, which served as toilets in times before 1940-50 in Blisworth. They

were sometimes referred to as 'offices' in around 1900. Sometimes the

privy was adorned with some humour as in the case of the Burbidge

Bros. (Timber Merchants) off the High Street.

The arrangement was that nearly all houses

either had their own privy, or a share of one, the bucket within which was periodically emptied

either onto the gardens, into a nearby cesspit or into one's 'dedicated' drain

extension if the house or yard was lucky enough to have one. Cesspits are

marked as blue dots and it is amusing to observe that two of them were located

very near to a public house. Drain extensions would have had an iron lid to

keep smells down. Incidently, if this website stands a

good chance of surviving 50 years, there will be nobody to define 'privy'.

The attached pictures are therefore provided to place

on record the grim, cold and roughly-shod sheds, set at some distance from the

house, which served as toilets in times before 1940-50 in Blisworth. They

were sometimes referred to as 'offices' in around 1900. Sometimes the

privy was adorned with some humour as in the case of the Burbidge

Bros. (Timber Merchants) off the High Street.

The cesspits and drain extensions would have been periodically

washed down into the pipes. Note that in two locations the sewage

was discharged into the canal, perhaps via a solids trap. In another, the

situation is even worst because it went into the minor stream formed by the

overflow from the canal - see northern edge of the map. In 1890 this

network require repairing and a settling tank was planned before discharge into

the stream. The tank was to be 16 by 20 feet and located low down in the field opposite the Baptist

terrace of houses in Chapel Lane. This settling tank simply overflowed

into the same stream - Wash Brook. Presumably the ultimate aim was to

reconnect the lower High Street pipes in a manner that allowed them to discharge

into the same settling tank. Gayton Road houses used an

"open ditch" which presumably also emptied into the Canal while the

Railway Cottage by the embankment had an "open ditch" going under the

road and joining to Wash Brook. Grafton House and any other property on the

Towcester side of the canal would not

have been able to have a cesspit on the main system because the connecting pipe

could not loop under the canal at West Bridge - they probably used a private

soilpit.

The settling tank to the north of Chapel Lane was about 5 yards

below canal water level. To marry an under-canal pipe to that tank would

have involved a low-level main pipe, following the old stream bed and a considerable length of spurs

connecting up to street level. Such a plan, in terms of a main which served

the village, was probably not put into effect until 1926.

By 1896, when the Parish Council began

their formal meetings, there were 15 cesspits which leads to the conclusion that

many drain extensions were shared and used as cesspits. At the NRO there is a map

of the location of the pits but the archivists report that the document is

rotted and cannot be handled. One can speculate the map was used 'in the

field' and so was not particularly well looked after! Thorough flushing of

all the pipes was called for by the Council in 1896, 1898 and in 1899. The issue was

not mentioned again. In 1898 the

Council considered a 'Night Soil' carting service in view of the pressure on the

system but at 3 shillings per night they dropped the idea. In 1900 and in

1904 the outflow from the tank into Wash Brook was obviously taking solids with

it. On both occasions Wash Brook had become choked between the village and the

embankment and was demanding attention. The man in charge of emptying the tank was sacked for neglect on one

occasion. In 1903 it was resolved by the District Surveyor that any

discharge from a WC into the canal must cease. This meant that much of the

early sewers would need modifying. In 1909 Wash Brook became choked on

the other side of the embankment for the first time.

In June1922 there was tabled a new sewage

scheme for the village but it was not planned to extend it to the Westley Buildings. It

is doubtful much was done then. In 1922 - 24 there was much concern about

the new Bacon Factory putting a large load onto the sewage system. It

seems unlikely that anything was done immediately with the arrival of the bacon

factory, for in 1925 Milton Malsor officially complained about "the bad

state of the brook". A major rebuild of the system took place in

1926. Up until then the brook passed under the railway through two

parallel culverts which were designed by the railway engineers to cope with the

wide range of flow experienced in the brook. In 1926, one culvert was dedicated to

carrying a large diameter sewer pipe, the one to the right as viewed from the

village side, and the sewage farm was then sited on the other side of the

railway. The phrase 'sewage farm' was evidently coined to cover the better

technology and installations to decompose raw sewage in filtration beds and

settling tanks. We can surmise that a good low level main pipe was

installed in 1926 from the point where there was once direct discharge into the

canal behind the Sun Moon and Stars public house. An automatic siphon and

flush pump was placed on the other side of the canal near there so that sewage

from the Gayton Road side could be flushed under the canal and discharged into

the new low-level sewer. This provision allowed a service to the new

houses been built along the Towcester Road. The run-up to this

installation is discussed in a Grand Junction Canal Co.

letter of 1924. The presumed layout of sewers and pumping station and

collection sump are shown in this Google picture.

The collection sump is known (J. Payler) to be there somewhere but no-one has

located it recently! With the improvements, new houses began to be

equipped with water closets connected to the sewers from 1926 but it must be emphasized that a 'water

closet' is simply a pan which can be flushed with a bucket of water from a

nearby well (see below - the water supplies). Older houses continued to use their back garden privies up

until 1937 when some houses could be connected to the sewage system. New

houses such as the new council houses along the Courteenhall Road were given a

connection as they were built.

On the Towcester Road some houses, for

example the Freeston house, last on the left 'going up', was built in 1927,

immediately after the improvements. The houses on the right, going up,

were started around 1930 by a lone builder and with each sale he managed to

finance the start of the next. Alternate houses had wells in their rear

gardens and pairs of neighbours were expected to share these. Probably

every house had a 3' diameter cistern built at the

rear to collect rainwater with a hand-pump in the kitchen for use in the

sink. There is a photograph of the remains of one such cistern at

one of the houses in Towcester Road noted during building revisions circa Feb

2009.

The village continued to enlarge. In

1955 the 29 house council 'estate' was enlarged and acquired over 100 new houses.

Furthermore there was a new development at the south end of the Stoke Road

planned by 1957 (Greenside) and this was apparently a particularly critical one

for the sewage system on account of levels in Stoke Road. Following a

public meeting 11th April 1960, a complete

revision of the system was carried out, particularly for Stoke Road, and gave

the Acme Building Company further opportunity to hastily build on disturbed

ground. The revisions also allowed the development of the

fields between the village and the council houses (Buttmead, Windmill Avenue,

etc) and the field known as Pond

Bank. By 1969 this was all built up and the new sewer system coped well (with

the exception of Little Lane apparently). A few old hands often say that

the installers had got mixed up between storm water and sewage and it seems

likely that such faults are still with us to this day. Storm water is supposed to

discharge into Wash Brook near to Chapel Lane but after a deluge very little

evidence can be seen emerging from the 12" diameter culverts. As a village, we often

see our streets streaming in water because of some limitation in the storm water

drains and no doubt a good deal of storm water is invisible to us because it

runs into the sewers. In about 1980, the sewage

farm on the other side of the embankment was replaced by a pump so that sewage

could by piped all the way down the valley to the Swan Valley area, processed there and

discharged into the River Nene. Wash Brook is consequently a clean stream

now. It is worth just pointing out that before 1800 Wash Brook was the

direct continuation of Fisher Brook which collected water from Blisworth

Hill. In fact "Fisher Brook" is rather a new name for it - the old

name was South Gutter - 'gutter' being an old name for a stream. Once the canal was established, the only water

available for Wash Brook was the canal overflow weir at Candle

Bridge. In the early part of the

20th century, there must have often been conflict between the village and the

Canal Company, for in dry weather Wash Brook would carry very little canal

overflow and perhaps, at times, was only carrying run-off effluent from the

village settling tank. There certainly were a number of complaints from

the villagers of smells etc. and not just from Milton Malsor.

Water Supplies

The story of the water supplies for

Blisworth also shows the stress from enlargement of the village. In the

upper High Street and Stoke Road region, the houses are built on a thick layer

of ironstone and sand which acts as a water conduit. The

annexed picture was taken Oct 2006 outside the Post Office and shows the

ironstone substrate clearly. Beneath this layer

there is blue clay which is the substrate for the lower High Street. As

the clay is more or less impervious to water there is generally a plentiful supply to be had

as a result of digging wells only a few yards deep. Even in the clay it

has evidently proved possible to dig a reliable well, for example behind the

Sun, Moon & Stars Inn, so obviously the clay contains fissures.

The newly formed Parish Council formed a

Sanitation Committee in 1895. They asked for

a full report on the state of the wells in the village in June 1896 and the

Towcester Rural District Council (TRDC) commissioned a Mr. Salmon to do a

survey. His report, held at the NRO, spoke of wells as either good, poor, need clearing out

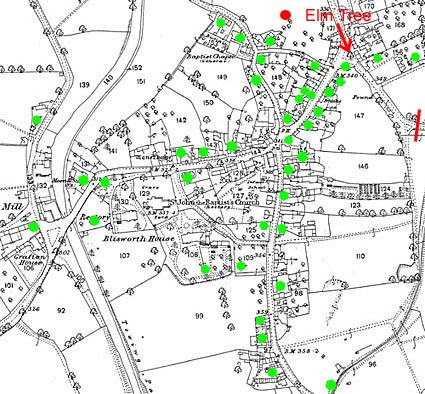

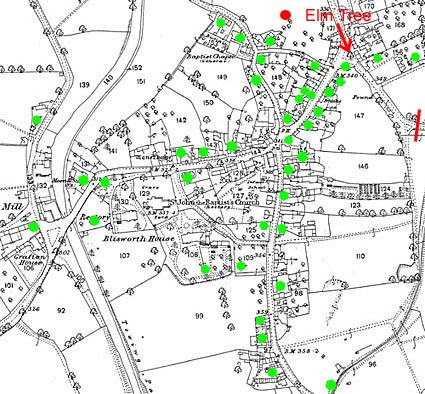

or undrinkable. He mentions 31 wells, rather fewer than the 39 indicated on the 1899

Ordnance Survey map, which are highlighted in green on the map here. Note

the scarcity of wells in the lower part of the village. Some properties have to rely on soft water collection

tanks, for example the Westley Buildings (according to Mr. Salmon) though there was a shallow well at the

Drum some 150 yards away but this was one which had been found undrinkable in

1895. A few wells, about 4, were reported as never failing and supplying a

large cluster of houses. One such was the well near the junction of Chapel

Lane with Little Lane. The houses lining the road to Towcester that were

built in the 1930s have a new well shared between each pair of houses.

The newly formed Parish Council formed a

Sanitation Committee in 1895. They asked for

a full report on the state of the wells in the village in June 1896 and the

Towcester Rural District Council (TRDC) commissioned a Mr. Salmon to do a

survey. His report, held at the NRO, spoke of wells as either good, poor, need clearing out

or undrinkable. He mentions 31 wells, rather fewer than the 39 indicated on the 1899

Ordnance Survey map, which are highlighted in green on the map here. Note

the scarcity of wells in the lower part of the village. Some properties have to rely on soft water collection

tanks, for example the Westley Buildings (according to Mr. Salmon) though there was a shallow well at the

Drum some 150 yards away but this was one which had been found undrinkable in

1895. A few wells, about 4, were reported as never failing and supplying a

large cluster of houses. One such was the well near the junction of Chapel

Lane with Little Lane. The houses lining the road to Towcester that were

built in the 1930s have a new well shared between each pair of houses.

There were political skirmishes in the

1890s as the brewers Phipps wanted the Parish Council to 'adopt' management of wells for the

cottages near the Sun, Moon & Stars. They resisted the suggestion as these properties

were held freehold by Phipps - ie. it was their problem. For the most part,

however, the wells in the village were owned by and maintained by the Duke of

Grafton. He was aging and running low on money before the WWI and it

proved necessary to send deputations to Pottersbury to get some

improvement. The chief difficulty year after year was that drought

conditions caused wells to fail and they had to locked up for most of the day.

The picture here shows the queuing that inevitably occurred in the bad draught

year of 1921. Furthermore, it appears that the ironstone mining had

damaged the water supply to the upper High Street area and this point is

returned to, as a footnote, at the end of this article. Yet another

concern was that although a particular well might contain water, the pump was

often broken. By October 1916 and after years of nagging, the Duke of Grafton conceded that all the wells maintenance

should be taken over by the Blisworth Parish Council.

There were political skirmishes in the

1890s as the brewers Phipps wanted the Parish Council to 'adopt' management of wells for the

cottages near the Sun, Moon & Stars. They resisted the suggestion as these properties

were held freehold by Phipps - ie. it was their problem. For the most part,

however, the wells in the village were owned by and maintained by the Duke of

Grafton. He was aging and running low on money before the WWI and it

proved necessary to send deputations to Pottersbury to get some

improvement. The chief difficulty year after year was that drought

conditions caused wells to fail and they had to locked up for most of the day.

The picture here shows the queuing that inevitably occurred in the bad draught

year of 1921. Furthermore, it appears that the ironstone mining had

damaged the water supply to the upper High Street area and this point is

returned to, as a footnote, at the end of this article. Yet another

concern was that although a particular well might contain water, the pump was

often broken. By October 1916 and after years of nagging, the Duke of Grafton conceded that all the wells maintenance

should be taken over by the Blisworth Parish Council.

The Parish Council in 1897 were of the

opinion that water quality and quantity had suffered as a result of the

ironstone mining, particularly at the top of the village. They lobbled for

both more wells or deeper and better headings to the existing wells to enhance

the supply. Nothing was done but there was a bold scheme suggested by an

engineer, a Mr. Roberts, brought in by the

Duke; that the high tank at the mill (Westley's

storage tank is still visible) could be used as a

soft water reservoir which would support a few stand-pipes in the lower

village. Then, working with this reservoir, Westley's steam power could assist collection from a number of

ground pipes which

would need to be laid out on the Towcester side of the village to collect

water. Roberts also came up with a scheme which included a windmill pump, the use of which seems hard to envisage in the

valley near the canal. The committee in December 1897 records "we

cannot see our way to doing what Roberts suggested" and thought little of

the scheme. They still wanted the Duke to improve the wells as a first

priority. One gets the impression that this refusal of the Duke's capital

expenditure actually damaged his willingness to maintain the wells.

Another problem encountered was that the

well outside where the new school would be built displayed the symptoms of

drought after the school was built. Furthermore its contamination by

faecal material ensured it was of no further use unless all water were

boiled. A layer of ironstone had been removed from the field just before

the school was built and this was once presumably a reasonably clean water conduit.

On the sale of the Grafton Estate in 1919,

the Parish Council took over ownership of the wells thus formalising their responsibility

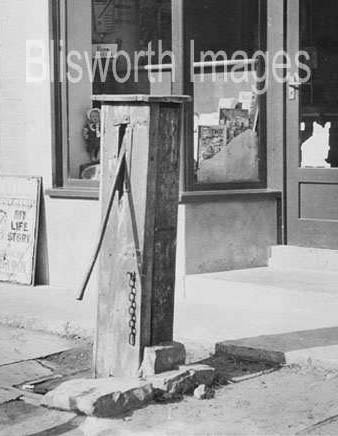

to maintain them. Amusingly, the pump and well located near

Alexander's green grocer shop was inadvertently sold by the Duke along with the cottage it was attached

to. A Mr Pinfold subsequently agreed to sell the well to the Council for a

consideration of £5 and in the George Freeston Collection there is to be found

the Deed of Sale. This was the pump that was carefully preserved, although

hardly potable, in 1950 when the house was demolished in order to build our

present newsagent's shop - see the picture alongside.

On the sale of the Grafton Estate in 1919,

the Parish Council took over ownership of the wells thus formalising their responsibility

to maintain them. Amusingly, the pump and well located near

Alexander's green grocer shop was inadvertently sold by the Duke along with the cottage it was attached

to. A Mr Pinfold subsequently agreed to sell the well to the Council for a

consideration of £5 and in the George Freeston Collection there is to be found

the Deed of Sale. This was the pump that was carefully preserved, although

hardly potable, in 1950 when the house was demolished in order to build our

present newsagent's shop - see the picture alongside.

In the 1930s there were a number of

council houses built. From a point of view of providing water, much

difficulty was experienced in sinking a successful well for the 29 houses needed

to accommodate the families from the Westley Buildings which had been

condemned. No drinkable water was found at all, yet the planners (actually merely some

Council members and one TRDC chief architect) resolved to build the 29 houses along

the Courteenhall Road anyway. Large soft water tanks were provided, each to be shared

between two families. These of course failed and the TRDC was forced to

deliver fresh water once or twice a week - an action that had actually started

in 1932, for a few houses, and continued right up to

the 1950s whilst piped mains water was still not provided for the village.

Northampton town was put onto mains water in 1938. The possible need for

more water deliveries was anticipated in 1936 and there was an uproar in the

village over "the injustice of some houses getting good water, by lorry, the full year

round". The measures were considered by some to be better than using the wells!

It is said that by 1948 so many new wells

had been dug that the total number was 49 "private" wells and 2 public

(but condemned) wells. It was perhaps in the 40s or 50s that a pump was set up in

a shed

over the tunnel mouth. The pump was to deliver water across two fields to

the back of the planned new council houses where a tank was set up on angle iron

framework (near to the group of garages). Whether this supply was much

help cannot be remembered.

It is said that by 1948 so many new wells

had been dug that the total number was 49 "private" wells and 2 public

(but condemned) wells. It was perhaps in the 40s or 50s that a pump was set up in

a shed

over the tunnel mouth. The pump was to deliver water across two fields to

the back of the planned new council houses where a tank was set up on angle iron

framework (near to the group of garages). Whether this supply was much

help cannot be remembered.

The late part of 1953 saw the installation

of mains water pipes in the village. In January 1954 the pipes were all

washed out and, as no doubt all villagers attentively looked on, the village was

gradually connected up. Ironically, the last houses to be connected

were the 29 houses still being supplied by lorry - they were not served until

1955.

Some householders have proudly kept their

wells whilst others have been closed off with a variety of materials either sound

and precarious. The pump by the newsagent was gone by 1954 and in November

1957 the pump outside the school was removed to leave a manhole cover by the

fence. In November 1964 the old school well was filled in and part of the

cavity used for drainage connections, another manhole cover indicating its

position at the top of the entrance steps.

The large private houses enjoyed the

benefit of a private well. On the Grafton House pages is mentioned the fact that

in c1890 land which included Ramwell Spring was farmed by the Westleys who lived

at Grafton House. A cast iron pipe was run from a tank all the way down the

hill, maybe ¼ mi, to the house thus supplying water at a quite high pressure.

The rectory (built 1841) has a well in an outhouse that is about 20' deep and

carries water to often a depth of 10'. There is a pipe with a leather gland

pump, located about 12' above the water level, driven by an electric motor which

used to pump fresh water up to the first floor of the main house. Before

electricity ~1927 there was probably a small steam engine fired up to do the job

- the layout of the equipment puts one in mind of an ingenious blacksmith. The

present water is a very clear blue coppery sulphate colour - not encouraging.

The school well was of the style shown in this picture.

The school well was of the style shown in this picture.

FOOTNOTE: Ironstone Mining

The effectiveness of a well should be partly dependant on water collected

under neighbouring land that has a higher elevation than at the well. For

the upper High Street area, the land on both sides of Courteenhall Road within a

few hundred yards of the Elm Tree would serve as a collection area but this was

all surface mined for ironstone 1870 - 1914. The mining took place on both

sides of the road, see map in the ironstone

section, and the two were linked by a rail line for horse-drawn wagons

which passed under the road a little to the east of the red line in the map above. That tunnel

for the rail would be a local low point and water from much of the mined area would collect

near there. In

1895 the Parish Council, while concerned about the shortage of water for the

village, stated that water associated with the mining area was

'inadequate' yet in 1899 a rather desperate idea was discussed to use the water

from precisely the place mentioned above. Upon reading that in the

minutes, the idea which sprang to mind was that of an open pool - with

the obvious concerns. The proposal was not taken up. Recently a

villager recalls being asked, by George Freeston, to dig near the red dot in the

map above to locate a 2½ foot brick culvert which was assumed to be a drain for

water from the tunnel under the road. The water was thought to run all the way down the slope of Courteenhall Road,

under a private garden (where the culvert had been accidentally detected and

breached during building works) and into the

stream then serving as the village top-water carry off ( including the water

issuing from the sewage settling tanks.) The culvert was supposed to

emerge from under the field a little lower down than the red mark, for George

had taken the attached photograph of a deep gully that had been etched into the

profile of the field. A 1970s farmer of the field thought there was a

spring there but that would not explain the gully in the photograph. The most likely

interpretation is that in around 1880 a culvert was built to lead the water away from the

mining area and into the field, so bypassing to some extent the wells in the High

Street. Decades of run off from the mining would have cut the gully. So it

is the end of the buried culvert that behaves like a spring?

Tony Marsh October 2006

The arrangement was that nearly all houses

either had their own privy, or a share of one, the bucket within which was periodically emptied

either onto the gardens, into a nearby cesspit or into one's 'dedicated' drain

extension if the house or yard was lucky enough to have one. Cesspits are

marked as blue dots and it is amusing to observe that two of them were located

very near to a public house. Drain extensions would have had an iron lid to

keep smells down. Incidently, if this website stands a

good chance of surviving 50 years, there will be nobody to define 'privy'.

The attached pictures are therefore provided to place

on record the grim, cold and roughly-shod sheds, set at some distance from the

house, which served as toilets in times before 1940-50 in Blisworth. They

were sometimes referred to as 'offices' in around 1900. Sometimes the

privy was adorned with some humour as in the case of the Burbidge

Bros. (Timber Merchants) off the High Street.

The arrangement was that nearly all houses

either had their own privy, or a share of one, the bucket within which was periodically emptied

either onto the gardens, into a nearby cesspit or into one's 'dedicated' drain

extension if the house or yard was lucky enough to have one. Cesspits are

marked as blue dots and it is amusing to observe that two of them were located

very near to a public house. Drain extensions would have had an iron lid to

keep smells down. Incidently, if this website stands a

good chance of surviving 50 years, there will be nobody to define 'privy'.

The attached pictures are therefore provided to place

on record the grim, cold and roughly-shod sheds, set at some distance from the

house, which served as toilets in times before 1940-50 in Blisworth. They

were sometimes referred to as 'offices' in around 1900. Sometimes the

privy was adorned with some humour as in the case of the Burbidge

Bros. (Timber Merchants) off the High Street. The newly formed Parish Council formed a

Sanitation Committee in 1895. They asked for

a full report on the state of the wells in the village in June 1896 and the

Towcester Rural District Council (TRDC) commissioned a Mr. Salmon to do a

survey. His report, held at the NRO, spoke of wells as either good, poor, need clearing out

or undrinkable. He mentions 31 wells, rather fewer than the 39 indicated on the 1899

Ordnance Survey map, which are highlighted in green on the map here. Note

the scarcity of wells in the lower part of the village. Some properties have to rely on soft water collection

tanks, for example the Westley Buildings (according to Mr. Salmon) though there was a shallow well at the

Drum some 150 yards away but this was one which had been found undrinkable in

1895. A few wells, about 4, were reported as never failing and supplying a

large cluster of houses. One such was the well near the junction of Chapel

Lane with Little Lane. The houses lining the road to Towcester that were

built in the 1930s have a new well shared between each pair of houses.

The newly formed Parish Council formed a

Sanitation Committee in 1895. They asked for

a full report on the state of the wells in the village in June 1896 and the

Towcester Rural District Council (TRDC) commissioned a Mr. Salmon to do a

survey. His report, held at the NRO, spoke of wells as either good, poor, need clearing out

or undrinkable. He mentions 31 wells, rather fewer than the 39 indicated on the 1899

Ordnance Survey map, which are highlighted in green on the map here. Note

the scarcity of wells in the lower part of the village. Some properties have to rely on soft water collection

tanks, for example the Westley Buildings (according to Mr. Salmon) though there was a shallow well at the

Drum some 150 yards away but this was one which had been found undrinkable in

1895. A few wells, about 4, were reported as never failing and supplying a

large cluster of houses. One such was the well near the junction of Chapel

Lane with Little Lane. The houses lining the road to Towcester that were

built in the 1930s have a new well shared between each pair of houses.

There were political skirmishes in the

1890s as the brewers Phipps wanted the Parish Council to 'adopt' management of wells for the

cottages near the Sun, Moon & Stars. They resisted the suggestion as these properties

were held freehold by Phipps - ie. it was their problem. For the most part,

however, the wells in the village were owned by and maintained by the Duke of

Grafton. He was aging and running low on money before the WWI and it

proved necessary to send deputations to Pottersbury to get some

improvement. The chief difficulty year after year was that drought

conditions caused wells to fail and they had to locked up for most of the day.

The picture here shows the queuing that inevitably occurred in the bad draught

year of 1921. Furthermore, it appears that the ironstone mining had

damaged the water supply to the upper High Street area and this point is

returned to,

There were political skirmishes in the

1890s as the brewers Phipps wanted the Parish Council to 'adopt' management of wells for the

cottages near the Sun, Moon & Stars. They resisted the suggestion as these properties

were held freehold by Phipps - ie. it was their problem. For the most part,

however, the wells in the village were owned by and maintained by the Duke of

Grafton. He was aging and running low on money before the WWI and it

proved necessary to send deputations to Pottersbury to get some

improvement. The chief difficulty year after year was that drought

conditions caused wells to fail and they had to locked up for most of the day.

The picture here shows the queuing that inevitably occurred in the bad draught

year of 1921. Furthermore, it appears that the ironstone mining had

damaged the water supply to the upper High Street area and this point is

returned to,  On the sale of the Grafton Estate in 1919,

the Parish Council took over ownership of the wells thus formalising their responsibility

to maintain them. Amusingly, the pump and well located near

Alexander's green grocer shop was inadvertently sold by the Duke along with the cottage it was attached

to. A Mr Pinfold subsequently agreed to sell the well to the Council for a

consideration of £5 and in the George Freeston Collection there is to be found

the Deed of Sale. This was the pump that was carefully preserved, although

hardly potable, in 1950 when the house was demolished in order to build our

present newsagent's shop - see the picture alongside.

On the sale of the Grafton Estate in 1919,

the Parish Council took over ownership of the wells thus formalising their responsibility

to maintain them. Amusingly, the pump and well located near

Alexander's green grocer shop was inadvertently sold by the Duke along with the cottage it was attached

to. A Mr Pinfold subsequently agreed to sell the well to the Council for a

consideration of £5 and in the George Freeston Collection there is to be found

the Deed of Sale. This was the pump that was carefully preserved, although

hardly potable, in 1950 when the house was demolished in order to build our

present newsagent's shop - see the picture alongside. It is said that by 1948 so many new wells

had been dug that the total number was 49 "private" wells and 2 public

(but condemned) wells. It was perhaps in the 40s or 50s that a pump was set up in

It is said that by 1948 so many new wells

had been dug that the total number was 49 "private" wells and 2 public

(but condemned) wells. It was perhaps in the 40s or 50s that a pump was set up in