|

The Mill Fire, Blisworth 1879

Aprons of dim gold

extended across the roads as darkness fell. The snow thickened and

deepened by evening and the few remaining men at the mill tidied up the front

shop and oven room for tomorrow's bake which would start at five. They

were always bedevilled by insufficient flour, so again the boiler, grinder, the mill

and screens would have to be tended by Will and Elijah - probably until four. The two

went to work and

when they had got three sacks of flour, about half way, they stopped

again. And so it was that Elijah Clarke, with a little too much drink, fell asleep in the early hours while the machines ran through the last bags of corn that he had put in the hopper. Elijah was far away when something broke on the grinder and a shower of sparks cascaded onto the mill floor. The sparks continued until the shear pin broke. The grinder stopped and the mill fell silent. No new sparks . . . Fireflies had begun running in abandon over the mass of old twine and then inside the mass and from there to a hemp sack - gradually blackening, expanding and expanding. At half past two some small flames sprang up to devour the remaining twine with its wisps of charcoal. The patient flames died down again whilst the dried out sack lay with its secret within. Suddenly the sack came alive with more flames which had flashed over it and then expanding rapidly to devour it. More sacks followed the first until the machine room, with dense white smoke pouring from the high vents, was being dried by the flames. Suddenly the screens and a mass of loose flour blew up in a bright yellow flash and puffs of burning dust shot out of every crack in the building; a moment of yellow illuminated the street, swallowed immediately by the snow, no one noticed it. By three o'clock, the timbers of the building were alight and some of the white smoke was being replaced by flickering flames. Outwardly there were also shafts of gold where the snow was picking out the light escaping from the intense within. The commotion within the building was smothered by the snow - even the roar seemed little more than that of a wind. But with the good luck which sometimes attends such disasters, the aroma of a good wood fire and some late night baking, as it would have seemed, caught the nose of just one man who had reason to be awake at after three . . . --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The Northampton "Mercury" continues the story: "On the morning of Thursday 4th January, 1879, the granary, mill and machinery of Messrs. Westley and Sons, of Blisworth, millers, were destroyed by fire. To those who do not know the premises it should be stated that the house and its appurtenances stand on the right of the entrance to a broad and long yard, and on the left are the business offices, the bakehouse, meal room, with garners above, mill, engine house and boiler. The buildings beyond the bakehouse are comparatively new, having been built within the last twenty years when the old windmill was thought by Westley to have insufficient output and be too expensive to keep. Communication with the meal room is effected by means of a door, which Mr. Westley, the senior of the firm, had suggested that in case of fire should be blocked up by flour bags. The dreaded contingency which had excited only passing apprehension at last arrived, for a fire broke out in the mill, near the bran machine, the only assignable cause being that of friction, and at three o'clock, or thereabouts, the inmates of the house were awakened by the driver of the mail cart as he was proceeding to Towcester. On arriving there he gave the alarm, and the members of the Fire Brigade were aroused. The Northampton Volunteer Town Fire Brigade were also sent for by Mr. Westley, who with Mr. G Stops, of Greens Norton, a relative, were soon up, and across at the fire, followed by Bert Hickson, one of the oldest workmen. The fire was first seen at the window on the far side of the gable of the milling premises, and in a room where there were three pairs of French stones, and one pair of Barley. The meal room, that is the lower part of the granary was next attacked, and the flames soon made such progress that the beams supporting the floor above gave way, and about 400 quarters of wheat and 100 quarters of other grain fell into the burning mass. Fortunately, Messrs Westley and Sons enjoyed the goodwill of the whole of their neighbours, and we are glad to say that the whole of them, farmers and cottagers alike, worked admirably; and had it not been for their exertions, coupled with the peculiar character of the weather, there would, in all probability, have been a widespread conflagration. The efforts of those who were engaged in extinguishing the fire were first directed to the bakehouse, the object being to restrict the fire to the granaries in the manner already indicated, and by means of water, of which buckets full were poured on the roof and walls from above, and ultimately the roofs of the burning pile fell in. Shortly after the fire brigades arrived, and though the progress of the fire had been arrested, they did most valuable service in playing upon the gutted premises. The Towcester Brigade had the honour of getting to the spot first, but Mr. Westley bears most satisfactory testimony to the first trial of the new steam fire engine at a fire. The hose was taken down to the canal, about a quarter of a mile off, and threw the water up from the low level of the canal in splendid style, while both brigades worked most praiseworthily under Captain J S Norman and Mr. Supt. Lines, who went over to the fire on hearing of it, with Inspector Henshaw of the County Police. It was fortunate that the fire was discovered thus early, as Mr. Westley was able to get the whole of his horses out of the stables opposite, where about 450 quarters of oats were stored. The buildings on the other side of the yard, indeed, did not suffer in the least, and although myriads of sparks were carried by the wind into Mr. Carter's rick-yard, the ricks, having received nature's thatching of snow, did not take fire. The snow was useful in other respects, for Mr. Westley happily bethought himself of setting a number of boys to work to snowball one part of the fire, and thus the snow, as it melted, served instead of water. "The fire had not been totally extinguished the next day, the premises presenting a sad spectacle. Grain, mixed with charcoal, and either scorched or parboiled lay in heaps below where it had been garnered, and the fowls refused to eat it. Two or three workmen were carting away spoiled flour such as had not been converted by the water into a paste or dough. The grinding stones, and the shafting twisted out of shape, were mingled with a blackened mass of ruins, and the engine house was a complete wreck, even the large flywheel, about 11 feet diameter, and weighing between two and three tons, being cracked, and the brasses and metalwork fused by the intense heat. The total damage is between £2000 and £3000, and we are glad to say that Mr. Westley is insured in the Miller's Fire Office, Birmingham. The entire stoppage of the works, and the difficulties attending the transference of the work to other mills will necessarily occasion great loss. The horses, as we have said, were removed in safety, but being much frightened by the occurrence, kicked a man named Clarke, who was attending them, on the cheek. The poor man is, however, going on well. This was the only accident of any importance at the fire, although work was done involving considerable risk. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- It was nearly

midday when Joseph Westley made a second survey of the mill works. He had

called George Groom, the millwright, to help him decide what to do. He was

puzzled by Elijah Clarke's telling him that all the machinery was shutdown by two

o'clock when he went to bed, though deciphering what he said through his broken jaw was not

easy. Resolving to leave Elijah alone for a while, he called a meeting

with his sons. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- George Groom did indeed refurbish the windmill that Ann Westley, with Mr. Rockingham helping, had run from about 1825 till the 1850s when the business was transferred to Joseph's new mill driven by steam. This steam mill in the Stoke Road would have used conventional stones in a row of pairs all belt driven from one overhead long shaft which extended through a gable into the engine room. In the 1870s, Joseph resolved to improve productivity using roller mills at Nunn Mill having spent some time in Austria and Hungary with 40 other millers of Northamptonshire learning of the advantages of rollers. One advantage was that the flour was cleaner of stone powder from the mill since the rollers were made of porcelain. Another was that the wheat-germ could be separated from the flour as it was ground more finely and this promoted a flour that would keep longer and give a more workable dough for bakers. Of course this meant that there was less "goodness" in the flour but this fact was more than balanced by a greater profitability for all but the final consumer.

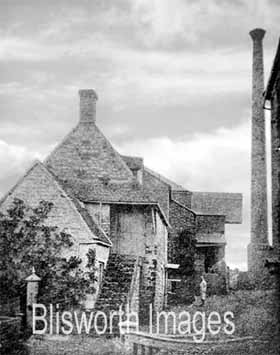

There seems little doubt that George Groom would have been able to expand his business based on a large expenditure by the Westleys. For not only was Westley building the new mill at Blisworth, he was engaging Groom to service their stone mill at Weston and (probably) expand the productivity of Nunn Mill in order to not loose market. The final stages of the millwright's account at Blisworth, which had amounted to near £500, was settled in March 1883. It is likely that Blisworth Mill's first production year was 1883, it seeming probable that Westley had prioritised work at Nunn Mill so as to retain market. The curious fact that the only company accounts book for Groom to descend to this day was the one which covered Westley's fire recovery might be explained in terms of Groom or his family keeping the record of a business project that truly 'set him up'. In the 20th century, the Groom's concern merged with Tattershall's and the combined company set up in a large engineering works near Towcester railway station. The site is now occupied by the Towcester branch of "Focus". Whether Westley was able to discover the cause of the fire, further than speculation about friction, and whether he thought anyone was to blame is not recorded anywhere. The fact remains that to suggest friction does imply that some machinery was being run overnight and raises the question why no-one saw the start of the fire. Joseph Westley was such an influential figure in the village that, no doubt, few people would be keen on airing such questions at all vociferously. A study of the subsequent issues of the Northampton "Mercury", up to the end of 1879, have revealed no follow up article that raised any questions at all. Joseph Westley perhaps looked back on the episode from 1879 to 1883 as a fortuitous opportunity to modernise his operations in Blisworth and a vital opportunity to revise his fire precautions. He moved to Grafton House at about this time so as to be near his new project. The bakehouse in the Stoke Road probably continued in use. Joseph Westley died in 1895 leaving the business in the capable hands of his sons. Ever larger mills placed at ports or otherwise near to good transportation were becoming important, so when the Duke of Grafton sold most of his holding in Blisworth in 1919 the Westleys sold the mill as a going concern to the Northampton Co-operative Society. The brothers had earlier sold the baking business to the Sturgess family and let the bakehouse to them. The Westleys eventually sold the site for the start of The British Bacon Company in 1925. The fine building by the canal ceased to be a mill in around 1930 with the folding up of the failed Co-op project. It was bought by the a canal carrying company and was used as a warehouse. In the war years it was taken over by the War Commission for Food. An interesting detail is that when the windmill was in use, for example in Dent's day, the straight-line path to it that is shown in the 1838 maps was reserved rentfree to the miller. When fields each side of the path were sold in the period 1919 - 1939 the path was forgotten by the Grafton agents. The path, to this day, belongs to the earl of Euston! --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The first section of this account is fictional, as is the character of Elijah Clarke. The millwright and a boy did in fact pay a short visit to the mill on the day before the fire. The extract from the Northampton Mercury newspaper is reproduced verbatim with one addition (given in italics). The interaction between Westley and the Duke of Grafton is referred to by GF. The role of millwright George Edward Groom (1858 - 1927) of Millwright Works, Eastcote, is constructed from a ledger in the possession of Mrs. S Phillips, who kindly allowed me to record from it. The characterisations of George Groom and Joseph Westley are both fictional. The date of the Stoke Road buildings photograph is not known - it could be pre-1879 or, just as likely, circa 1900 when the Sturgess family had taken over baking there. The photograph of the new mill includes a little of the boundary shrubs and the garden wall around Grafton House. Tony Marsh, 10 March 2006

|

It was

mid-afternoon, January 3rd, when it began to snow heavily. The sky had

turned a dark leaden blue. The failing light was being countered by the

bright shawls of snow draped over the thatched roofs and the brightening roads.

The snow strived to obliterate the pall of steam from Westley's mill

chimney and the village quietened as the chickens, dogs and cats scurried

for cover.

It was

mid-afternoon, January 3rd, when it began to snow heavily. The sky had

turned a dark leaden blue. The failing light was being countered by the

bright shawls of snow draped over the thatched roofs and the brightening roads.

The snow strived to obliterate the pall of steam from Westley's mill

chimney and the village quietened as the chickens, dogs and cats scurried

for cover. The Windmill: This is recorded as follows (from compilation of Midlands

windmills, Northamptonshire Record Society): post mill with two common and

two spring sails, brake and tail wheels. It worked in unison with the old steam mill in stoke

Rd until the latter burnt down in 1879. It was put up for sale in the same

year. George Groom's work

on this windmill, located off the Courteenhall Road, included replacing 25

wooden cogs in the "wallow-wheel" - the last in a train of gears from

sails to mill stones. He replaced two sails and charged for a long stout

pole, 13 inches square cross-section, of pitch pine which was probably part of the main drive extending downwards

from the head of the building. The mill may well have been ready for use

by April 1879 and by 1883 (see below) it would be ready to be abandonned and

sold. It is clear that Westley immediately talked to the Duke of

Grafton and secured a freehold on a large plot of land at the canal wharf near

the bridge. No doubt this freehold was offset to a degree by Westley

promising, in due course, to relinquish the freehold at the windmill. The

Duke thought him impetuous and declared that no one could build on that land so close to the canal. Westley proved him wrong and

in an amazingly short time - before the end of

the year - he had built, to a similar design to Nunn Mill, at least a massive shell of brick

carrying the date-stone for that year, 1879, high on the gable. Groom's account shows

substantial labour costs throughout the year and it is impossible to decipher

which of three tasks was being progressed at any time, viz. windmill refurbishment,

component salvaging at Stoke Road or the assembly of machinery at the Wharf, the last

being perhaps in a temporary wooden structure. We have no idea who was

charged with the bricklaying work. Groom's first mention of the new

works is for October 7th; "himself and two men, all day at the wharfe"

and that would be related to machinery and not building.

The Windmill: This is recorded as follows (from compilation of Midlands

windmills, Northamptonshire Record Society): post mill with two common and

two spring sails, brake and tail wheels. It worked in unison with the old steam mill in stoke

Rd until the latter burnt down in 1879. It was put up for sale in the same

year. George Groom's work

on this windmill, located off the Courteenhall Road, included replacing 25

wooden cogs in the "wallow-wheel" - the last in a train of gears from

sails to mill stones. He replaced two sails and charged for a long stout

pole, 13 inches square cross-section, of pitch pine which was probably part of the main drive extending downwards

from the head of the building. The mill may well have been ready for use

by April 1879 and by 1883 (see below) it would be ready to be abandonned and

sold. It is clear that Westley immediately talked to the Duke of

Grafton and secured a freehold on a large plot of land at the canal wharf near

the bridge. No doubt this freehold was offset to a degree by Westley

promising, in due course, to relinquish the freehold at the windmill. The

Duke thought him impetuous and declared that no one could build on that land so close to the canal. Westley proved him wrong and

in an amazingly short time - before the end of

the year - he had built, to a similar design to Nunn Mill, at least a massive shell of brick

carrying the date-stone for that year, 1879, high on the gable. Groom's account shows

substantial labour costs throughout the year and it is impossible to decipher

which of three tasks was being progressed at any time, viz. windmill refurbishment,

component salvaging at Stoke Road or the assembly of machinery at the Wharf, the last

being perhaps in a temporary wooden structure. We have no idea who was

charged with the bricklaying work. Groom's first mention of the new

works is for October 7th; "himself and two men, all day at the wharfe"

and that would be related to machinery and not building.